Debt Relief Is the Most Effective Pandemic Aid

Just as the pandemic can be contained most effectively and least expensively with aggressive early action, the lesson from the past is that global recessions and their human costs are best addressed quickly and boldly. A two-year debt-payment moratorium for every emerging and developing economy that needs help would serve both goals.

Suspend Emerging and Developing Economies’ Debt Payments

Leaders of the world’s largest economies must recognize that a return to “normal” in our globalized world is not possible so long as the pandemic continues its grim march. It is myopic for creditors, official and private, to expect debt repayments from countries where those resources would have to be diverted from combating COVID-19.

CAMBRIDGE – As the COVID-19 virus spreads globally, economic paralysis and unemployment follow in its wake. But the economic fallout of the pandemic in most emerging and developing economies is likely to be far worse than anything we have seen in China, Europe, or the United States. This is no time to expect them to meet their debt payments, either to private or official creditors.

With inadequate health-care systems, limited capacity to deliver fiscal or monetary stimulus, and underdeveloped (or nonexistent) social-safety nets, the emerging and developing world is on the cusp not only of a humanitarian crisis, but also of the most serious financial crisis since at least the 1930s. Capital has been stampeding out of most of these economies over the past few weeks, and a wave of new sovereign defaults appears inevitable.

We have been consistently arguing the urgent need for a temporary moratorium on all debt repayment by any but the most creditworthy developing or emerging sovereign debtors. The case for a moratorium for distressed sovereign borrowers has many similarities to that for households, small businesses, and municipalities.

Underscoring the urgency is the reality that the quarantine experience is starkly different in the developing world. In the vast slums of São Paulo, Mumbai, or Manila, quarantining can mean living in one small room with ten people, with little food or water and scant or no compensation for lost wages. If history is any guide, the supply disruptions that accompany the pandemic may soon be followed by food shortages.

More than 90 countries have already sought emergency funding from the International Monetary Fund’s Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) and World Bank resources. And in much of the developing world, the worst of the pandemic is not expected until later this year.

When that happens, the direct humanitarian and economic impact will come on top of the pandemic’s effects on global trade and commodity prices, which are already battering many emerging economies. The World Trade Organization expects global trade to decline by 13-32% in 2020. Oil-producing countries (and many more primary commodity producers) have been suffering the consequences of the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, sparking downgrades in sovereign credit ratings.

Leaders of the world’s largest economies must recognize that a return to “normal” in our globalized world is not possible so long as the pandemic continues its grim march. It is myopic for creditors, official and private, to expect debt repayments from countries where those resources would have to be diverted from the fight against COVID-19.

Deepening and prolonging the global depression is a very risky proposition. At a low point in the mid-1980s, emerging and developing economies accounted for about 18% of global GDP (in US dollars); in 2020, that share is 41% (and 60% if adjusted for purchasing power).

We recommend an immediate temporary moratorium on external debt repayments for all but “AAA”-rated sovereigns. By “external,” we mean debts issued under the jurisdiction of foreign courts, typically in New York or London. Debts issued under domestic law would be dealt with by countries themselves. For this kind of debt relief to be effective, it must be encompassing, including debts owed to the multilateral lenders, such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, sovereign creditors (Paris Club members and China), and private investors.

Ultimately, the debt of many countries will need to be restructured; there will be no alternative to a negotiated partial default. But courts and multilateral lenders are no better able to handle debt default en masse than hospitals can handle operating at ten times capacity. A temporary moratorium may provide the necessary bridge. In the best-case scenario, it might even prevent some defaults.

The World Bank and the IMF have vast experience with countries in debt distress, and in recent years have increasingly recognized that partial default is often the only realistic option, a point we stressed in much of our earlier work on external debt. It is a great tragedy that, following the 2008 global financial crisis, the eurozone failed to find a way to restructure Southern Europe’s debts beyond the Greek case – a course of action we strongly advocated at the time. Trying to enforce regular debt payments in highly irregular times can only lead to deeper and more protracted recessions than need to happen.

Of course, a debt moratorium will require the US, which wields effective veto power at the IMF, to get on board. But so, too, must China.

In the past two decades, more and more developing countries turned to China for loans (which are typically collateralized and carry market interest rates). Although China is now a major creditor in about 40 countries and an important one in scores more, it has so far refused to join the Paris Club (which coordinates rescheduling of sovereign debts) and insists on pursuing its own bilateral closed-door approach.

What can be done? The IMF and the World Bank have the capacity and expertise to coordinate a debt moratorium if the US and other major players conclude that a such a move is in their national interest. Private creditors will have relatively little choice but to cooperate in the short run. Many emerging and developing economies will soon stop paying their debts, anyway. The world needs to get in front of the problem.

Saving the Developing World from COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic could devastate parts of the developing world. But with a concerted, cooperative, and holistic approach, the international community can avoid a large-scale humanitarian tragedy in vulnerable regions – and protect the rest of the world from destabilizing blowback.

LAGUNA BEACH – Declining coronavirus infection rates and plans to begin easing lockdown measures in some parts of the developed world have provided a ray of hope after weeks of unrelenting gloom. But, for many developing countries, the crisis may barely have begun, and the human toll of a major COVID-19 outbreak would be orders of magnitude larger than in any advanced economy. With the United States having recently recorded more than 2,000 deaths in a single day, this is no trivial number. If the international community doesn’t act now, the results could be catastrophic.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a case in point. Several countries there would face significant challenges in enforcing social-distancing rules and other measures to flatten the contagion curve. The region’s already-weak health-care systems could thus quickly become overwhelmed by an outbreak, especially in a high-density area.

Africa has long suffered from a severe shortage of health-care workers, with only 2.2 workers per 1,000 people (compared to 14 per 1,000 in Europe) in 2013. And few African countries have a meaningful supply of ventilators, a crucial tool for treating serious cases of COVID-19. Nigeria is reported to have fewer than 500 in total, while the Central African Republic may have no more than three.

Moreover, Sub-Saharan African governments have little fiscal and monetary space (or operational capacity) to follow the advanced countries in countering the massive impact of containment measures on employment and livelihoods. Spillovers from Asia, Europe, and the US – including depressed commodity revenues (due to declining demand and prices), rising import costs, a collapse in tourism, reduced availability of basic goods, lack of foreign direct investment, and a sharp reversal in portfolio financial flows – have already exacerbated these constraints. For those who had access to international capital markets, terms have become notably more onerous.

While Sub-Saharan Africa is not without some defenses – including strong family networks and cultural resilience, as well as lessons learned from the Ebola crisis – there is a real risk that this COVID-19 shock would lock it in a race between deadly hunger and deadly infections. Some states, already rendered fragile by decades of weak political leadership or corrupt authoritarianism, may even fail, which could fuel violent unrest and create fertile ground for extremist groups.

The risks are not limited to the short term. Countries are also vulnerable to major future productivity losses, via both labor and capital. Prolonged school closures and joblessness could contribute to increases in domestic violence, teenage pregnancies, and child marriage, especially in countries that lack basic infrastructure for remote schooling.

Simply put, Sub-Saharan Africa may be about to confront a human tragedy so profound that it could leave a generation adrift in some countries, with consequences that extend far beyond the region’s borders. Two examples perfectly illustrate the multifaceted spillover risks.

First, by drastically reducing Africans’ current and future economic prospects, the COVID-19 crisis could eventually fuel even more migration than current forecasts anticipate. Second, by triggering a series of corporate- and sovereign-debt defaults, an uncontrolled COVID-19 outbreak could exacerbate the financial-market instability that the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank have taken such strong action to repress. This increases the chances of reverse-contamination from the financial sector to the real economy.

The scale of the threat is not lost on the International Monetary Fund, which, through an enormous ongoing effort, has moved quickly and boldly to increase emergency funding. More than 90 developing countries have already approached the IMF for financial assistance. Together with the World Bank, the Fund has also called for official bilateral creditors, including China, which has become a major creditor in recent years, to suspend debt payments by the poorest developing countries. Leading the way here too, the IMF is providing immediate debt relief for 25 of its low-income member countries, using grant resources to cover their multilateral debt-servicing obligations for six months.

Meanwhile, some countries, such as China, have offered large in-kind medical donations (what less charitable observers have described as “facemask diplomacy”).

But, to stave off disaster in vulnerable regions, the international community must do a lot more. Advanced economies, in particular, should supplement the home bias that has (understandably) characterized their responses so far with a broader assessment of the global effects, including spillovers to and spillbacks from Africa. They should expand official funding assistance, facilitate broader debt relief, and urgently establish an international solidarity fund which other countries and the private sector could join.

Furthermore, developed countries should do more to share best practices for containment and mitigation of the pandemic. To facilitate this process, the World Health Organization needs to do a better job of centralizing and disseminating relevant information. Advanced economies’ leadership, one hopes, will soon extend to the universal deployment of more effective medical treatments, or even a vaccine.

Finally, the international community must do a lot more to crowd in private-sector resources. Much as it did in the developed countries, the private sector can play an important role in the crisis response in vulnerable regions, both directly and through proliferating public-private partnerships. While pharmaceutical and tech companies will do a lot of the heavy lifting, private creditors can help by working on orderly ways to reduce the immediate debt burden on more challenged developing countries.

But, again, this will require greater emphasis on enabling mechanisms. A bigger shift in mindset on the part of multilateral lenders and other international bodies (including the World Bank) will be needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic threatens to devastate large parts of the developing world. Only with a concerted, cooperative, and holistic approach can the international community avoid a large-scale humanitarian tragedy – and protect the rest of the world from destabilizing blowback.

COVID-19 Thrives on Inequality

Although the coronavirus affects everyone, it has exposed extreme global inequalities more profoundly than any previous crisis, because it directly exploits those inequalities. Only a massive increase in rich-country support for developing countries can stop the pandemic and prevent a global economic collapse.

NAIROBI – “The virus will starve us before it makes us sick.” That text message, which a colleague of mine in Nairobi received from Micah, a taxi-driver friend, encapsulates the existential threat that the COVID-19 pandemic poses to millions of people.

Micah hasn’t had a fare in weeks and is now borrowing money to buy food for his children. His business, like many others, has collapsed because of Kenya’s 19:00-05:00 curfew, the disappearance of tourism, and the closure of airports, bars, restaurants, and shops.

The International Monetary Fund has already said that the pandemic’s economic impact is “way worse” than that of the 2008-09 global financial crisis. In fact, new research by Oxfam, King’s College London, and the Australian National University shows that the current crisis could push as many as a half-billion people into poverty. And researchers at Imperial College London previously warned that COVID-19 could kill 40 million people unless governments took urgent action.

This virus affects us all, including princes and film stars. But never has a crisis so profoundly exposed the extreme inequalities that divide our world.

In Exodus-like scenes, millions of workers have been sent home without pay. Consider the female garment workers in Bangladesh who make many of the clothes that we wear. Ninety-eight percent of buyers, often rich multinational companies, refuse to contribute to the cost of paying their lost wages. What will these women do now?

Meanwhile, workers in essential roles – such as carers, nurses, and supermarket cashiers – can’t isolate themselves from the deadly virus and have some of the lowest-paid and most insecure jobs. Most of them are women, too.

Privileged citizens can get the best health care, rely on their savings, and work at home (or escape to a holiday home) during the pandemic. But for most of humanity, such relative safety is well out of reach.

As with inequality within countries, inequality between rich and poor countries will radically shape people’s experiences of this pandemic. While rich-country governments unveil huge financial packages to save their economies, developing countries are drowning in debt, which has reached an all-time high of 191% of their combined GDP. Such inequality helps to explain why Tanzania has one doctor for every 71,000 inhabitants, and Mali has three ventilators per million. In refugee camps where Oxfam works, hundreds of people share a single water tap.

We need global action now. Only a mighty response by rich, powerful countries will stop the pandemic and prevent a global economic collapse. The G20 must live up to its mandate to lead the world through crises.

To that end, Oxfam’s Economic Rescue Plan For All urges the world’s richest economies to increase massively their support for developing countries, echoing the United Nations call for the creation of a $2.5 trillion global emergency-assistance package. In short, rich-country governments must take urgent steps to internationalize the measures that many of them are pursuing at home. This is not only the right thing to do, but is also in their self-interest. As long as the virus is anywhere, it is a threat everywhere.

The first priority is to unlock the trillions of dollars that poorer countries need. Here, the G20 must agree to cancel permanently all developing-country external debt due in 2020. It makes no sense for rich countries to be collecting money now from poor countries that need every shilling, peso, and rupee to fight the pandemic.

In addition, the G20 must pursue an emergency economic stimulus of at least $1 trillion in Special Drawing Rights, the IMF’s global reserve currency. This will boost the reserves of the world’s poorest countries while not costing rich countries anything – in fact, they, too, will benefit. The G20 must also champion increases in aid and emergency taxes, for example on extraordinary profits and speculative financial products. If now is not the time for such measures, when is?

The next priority is to direct the necessary resources toward saving lives and rescuing people from poverty. Increased funding will not help vulnerable populations if it is spent on the wrong things or is captured by unaccountable corporate elites. That is the core lesson of the 2008-09 financial crisis.

Oxfam has proposed a Global Public Health Plan and Emergency Response package that calls for an immediate doubling of public-health spending in 85 poor countries in order to save lives. In addition, governments need financial assistance to increase social protection, which four billion people worldwide currently lack, and to provide people like Micah with cash grants.

Economies everywhere need small businesses such as Micah’s to survive and help drive the eventual recovery. Bailouts for the richest companies, on the other hand, should be conditional on these firms paying their fair share of taxes, paying workers a living wage, and cutting their greenhouse-gas emissions.

Finally, as we begin to lay the foundations of the new in the ashes of the old, we should ask how we got to this point. Was it ever a good idea for governments to make health care a privilege of affluence rather than a fundamental right, or to ignore the necessity of a living wage or social protection for all? And was it ever smart to let two thousand billionaires own more wealth than 4.6 billion people combined?

Today, our planet is in crisis, and the health and economic wellbeing of its people are in deep peril. We cannot now carry on with the unequal, extractive, sexist, and rigged economic model that broke our world in the first place. Instead, we must build a more equal, sustainable, caring, and human-oriented economy, starting now.

Viral Inequality

Far from merely reflecting an unequal distribution of economic means, rising inequality comes with a broad range of additional toxic side effects, many of which the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown into sharp relief. With the pandemic transforming life around the world before our eyes, this is a problem that can no longer be ignored.

LONDON – Not everyone experiences pandemics in the same way. A tiny sliver of the world’s population has access to high-quality health care should they succumb to infection. Most of those performing low-paying shift work or agricultural jobs do not. People suffering from chronic disease such as obesity, diabetes, or cancer – including roughly 60% of American adults and a rising proportion of their African, Asian, and Latin American counterparts – are more at risk of dying than those who are younger and healthier.

The COVID-19 pandemic is serving as a stark reminder of the many inequalities that exist between and within countries. While virtually everyone will suffer from the disease – including wealthier people who picked up the coronavirus while travelling – the poor will be the most affected. Hundreds of millions of people are at risk of severe illness in low-income countries, most of which lack the economic resources and medical infrastructure to fight back against the virus. No part of the world will be more in need of support than Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

Even before the coronavirus outbreak and its dramatic transformation of all our lives, inequality was already one of the most incendiary issues on the global economic agenda. In addition to being a core grievance of populists and street protesters just about everywhere, it has also been at the center of a flagship United Nations report, and has even become a leading concern of business leaders surveyed in the World Economic Forum’s 2020 Global Risk Report.

So, the scale of global concern with rising inequality is entirely justified. After all, inequality is a key contributor to the political gridlock, social anxiety, and rising tide of nationalism that has swept the world in recent years, and which is now complicating the response to the COVID-19 crisis. Inequalities in income and wealth, access to health and child care, and many other domains will now shape the trajectory of the pandemic over the coming months and years, especially when fatality rates begin soaring in communities suffering from acute deprivation and disadvantage. Social isolation simply is not an option for multiple family members crowded into a single-room home or for those who must commute to put food on the table.

Setting the Stage

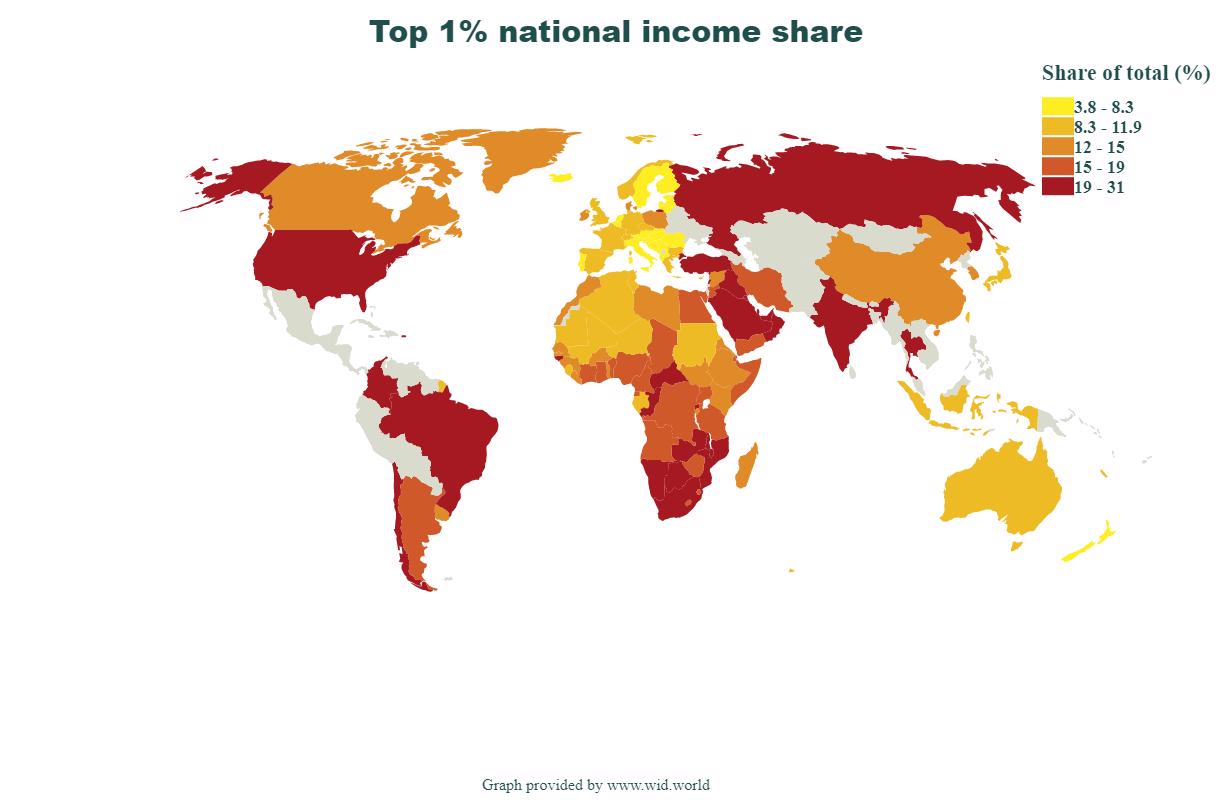

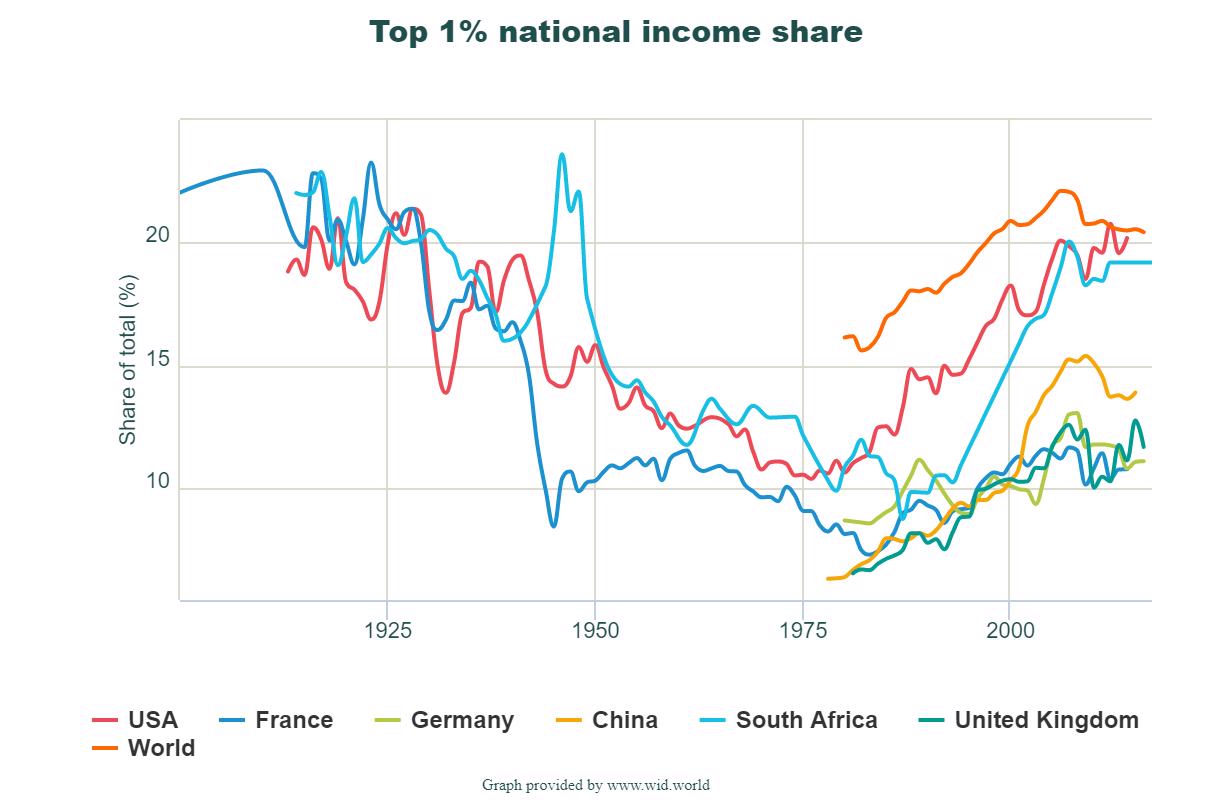

The story of international inequality in recent decades is not straightforward. Income and wealth gaps between countries have actually narrowed, a sign of progress in many lower- and middle-income settings. Yet levels of inequality within countries are steadily rising. A tiny elite – the so-called 1% – is pulling away from the rest pretty much everywhere, and not just in rich Western countries, but in poorer ones as well.

The fact that the super-rich emerged unscathed from the 2008 financial crisis has contributed to simmering resentments among a middle class that suffered deeply from that episode. When the rich flaunt their wealth – including fleeing to their bunkers and remote islands when faced with a crisis, jumping the queue to get tested for COVID-19, or disproportionately benefiting from treatment and care – public anger and discontent predictably will grow. When poorer people cannot afford to buy bread, much less a hospital bill, their anger turns to protest and radicalism. The situation has the makings of a political and social time bomb.

The first dimension of the inequality story – declining inequality between countries – is the natural result of developing countries growing much faster than richer countries. On average, incomes have long been converging globally. The other dimension – rising inequality within countries – has several causes. The main reason, however, is a matter of public policy: governments have cut taxes for the wealthy while slashing social and economic-redistribution policies that benefit those at the middle and bottom of the income distribution.

The regressive policies driving inequality within countries started during the era of US President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, and continued into the years of US President Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Elsewhere, in countries where virtually everyone was poor in the 1970s – Brazil, China, India, Russia, and South Africa – poverty reduction since the 1990s has been accompanied by soaring incomes among a thin wedge of elites.

Long before COVID-19 started spreading around the world, within-country inequality was growing at different speeds depending on where one looked. Since the 1980s, it increased most rapidly in China, India, Russia, and North America, and grew more moderately in western Europe.

Income inequality remained stubbornly high but stable in the Middle East, in large Latin American countries like Brazil, and in much of Sub-Saharan Africa. It shot up from already high levels in countries like South Africa, which is now ranked as the most unequal country on Earth. The different speeds at which inequality grew within countries reflects their unique economic circumstances and their particular blend of policies for managing trade, deregulation, taxation, public spending, and redistribution.

It’s Complicated

Further complicating the global picture, a few very large countries are exerting an outsized effect on global inequality. Consider the cases of China, Brazil, India, and Indonesia. Collectively home to more than three billion people, these countries account for humanity’s largest-ever reduction in extreme poverty over the past four decades.

In China alone, average incomes have doubled for each of the past four decades, pulling more than 800 million people out of deep poverty. In the 1980s, East Asia accounted for roughly half of all people living in extreme poverty (defined by the World Bank as an income below $1.90 per day), compared to just 9% today. Still, large pockets of deprivation remain. Roughly one-tenth of the world’s population lives in extreme poverty, including over 420 million people in Africa.

Meanwhile, wealth has become increasingly concentrated at the very top globally. According to Oxfam, between 1980 and 2016, the world’s richest 1% captured twice as much as the bottom 50%. During that time, the lower-middle class experienced improvements (especially in China), while the bottom 10% experienced little change.

But since the 2008 financial crisis, with some exceptions, job losses and stagnating wages have persisted, and yawning inequalities within countries have deepened, creating widening divides between the haves and have-nots. In the United States, for example, the incomes of the top 1% have risen seven times faster than those of the bottom 20%, and the top 0.1% now takes in 188 times more than the bottom 90%. Globally, the combined wealth of the richest 2,200 billionaires in 2019 exceeded $9 trillion, the equivalent of the total income of the poorest 160 countries combined.

Wealth is also concentrated geographically. One-quarter of the world’s billionaires now live in the US, and Chinese billionaires will soon outnumber European ones. These trends represent a clear failure to prevent a small minority from capturing the value added of economic growth. Unfortunately, this story is not new. In the US, real (inflation-adjusted) wages have been more or less stagnant for almost half a century despite ongoing growth. While top earners have seen their incomes rise substantially, lower- and middle-class laborers have fallen further behind.

A Recipe for Disaster

The inability to translate economic growth into higher wages is dangerous. Like climate change and pandemics, inequality is a threat magnifier, and has already contributed to growing anger and instability around the world. Higher levels of economic inequality tend to erode support for democracy and democratic institutions across all social classes. It is little wonder that trust in government, political parties, and state services has plummeted – especially in liberal democracies – over the past decade.

Lost public trust sets the stage for deeper social and political unrest. Although frustrations will play out differently in each country, popular outrage tends to seize on issues of state corruption and excessive concentrations of power and privilege in the hands of a distant elite. Anger about inequalities in income, housing, schooling, and political power has been a common thread of mass demonstrations in Bogotá, Hong Kong, Johannesburg, Istanbul, Paris, and Santiago throughout 2019.

Inequality is also bad for the economy, because it creates a downward spiral of slower growth, political paralysis, and polarization. The greater the inequality, the more constraints there tend to be on talent, social mobility, and access to skills training and education. These limitations undermine productivity and ultimately stunt economic growth.

At the same time, the political volatility generated by inequality creates uncertainty, thereby undermining investment and business confidence. According to the International Monetary Fund, a one-percentage-point increase in inequality decreases long-run national GDP by 2.5-3%, on average, for middle-income countries.

It is not just economic inequalities, but also gender- and ethnic-based disparities that hamper growth. In most countries around the world, women earn about one-quarter less than men for performing the same job. Meanwhile, other inequalities remain hidden, including the daily constraints experienced by elderly and disabled people and the discrimination against sexual minorities and other groups on the basis of race, caste, and religion.

Unequal and Unsafe

There are spatial and temporal dimensions to the global inequality story as well. For example, if measured by Gini coefficients, despite improvements, Latin America is one of the world’s most unequal regions. Moreover, beneath the surface, there are deep urban-rural divides around the world. Major cities are also major drivers of inequality. Vibrant cities such as São Paulo, Stockholm, and Sydney act as magnets, absorbing capital and talent from other cities and the hinterland.

But even within cities, where one is born and raised correlates strongly with one’s income later in life. For example, the closely connected neighborhoods of Pinheiros and Parelherios in São Paulo individually register human-development scores similar to those of Switzerland and Iraq, respectively. Inequalities in income and access to high-quality education and health care also correlate with more unplanned teenage pregnancies and higher infant mortality rates.

The extent of inequality often makes the difference between life and death. In Brazil, a one point increase in the Gini coefficient translates into 32 more births per 10,000 girls between the ages of 15 and 19. And these newborns are at a higher risk of premature death: a 1% increase in the Gini coefficient is associated with a 3% higher infant-mortality rate.

Higher inequality also has disturbing side effects in the form of violent crime and armed conflict. According to a 2002 World Bank study, inequality predicts around half of the variance in murder rates around the world. This is painfully obvious in the Americas, where over 40% of all the world’s homicidal violence occurs. In Mexico, a one-point increase in the Gini coefficient translates into a 36% increase in the homicide rate. In the US, multiple measures of inequality correlate strongly with higher firearm homicide rates across all ethnicities.

Around the world, economic, educational, ethnic, and gender inequalities between various groups increase the risk of armed conflicts breaking out. There is even evidence that the larger the gaps in income and other forms of inequality, the higher the rates of reported victimization. This may help to explain why South Africa and a number of countries and cities in countries such as Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico experience above-average levels of collective and interpersonal violence.

A Gallup poll asked almost 150,000 people in 142 countries about their perceptions of crime and safety across four measures: whether they had been assaulted in the previous year; whether they felt safe walking home at night; whether they have had property stolen; and whether they trust the local police. When these results were tested against each country’s Gini coefficient, they revealed a strong and positive relationship. In Venezuela, over 80% of the population does not feel safe walking home, whereas 95% of Norwegians feel the opposite. Finally, inequality has been linked to a range of other externalities from increased obesity and anxiety to higher rates of mental illness and suicide.

No Silver Bullet, but Also No Secret

Given all of the evidence of the harms wrought by rising inequality, it is clear that closing the gaps between the haves and have-nots should be a top priority for policymakers. Besides, there are many ways to reduce inequality that also would generate significant positive economic effects, as well as health, education, and security benefits. But there is no silver bullet. As the 2019 UN Human Development Report shows, policies to boost income and improve redistribution are necessary but not sufficient. Each country also needs a wide array of measures to reduce disparities and improve opportunities, especially for the poorest and most vulnerable.

Specifically, governments, businesses, and civic organizations need to do much more to correct the imbalance in services that rich and poor neighborhoods receive. There also need to be stronger policies and more investments in employment and income opportunities for deprived communities, and in health, education, and social protections. These issues will not go away after the COVID-19 pandemic recedes.

We know that these kinds of inequality-reduction interventions work. In Latin America, improvements in educational coverage – especially in early childhood and secondary schooling – have helped to reduce the earnings gap between skilled and low-skilled workers. And similar other strategies have been used to transfer more income to the poor (though that progress tapered off after the commodity boom of the 2000s).

Fortunately, many of the measures needed to address inequality are already encapsulated in the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and other initiatives like the Pathfinders for Peaceful, Just, and Inclusive Societies. Smart strategies span the gamut from increasing the minimum wage and expanding collective-bargaining power to ending discrimination against women and girls. Most of these interventions would rely on higher, more progressive income taxes, earned-income discounts at lower income levels, taxable child benefits, and universal minimum income policies.

Even when unlimited quantitative easing, job guarantees, and basic-income programs are launched to mitigate the economic fallout of COVID-19, improving tax collection will be crucial to ensure that governments have the funds needed to invest in health, education, and social wellbeing. In OECD countries, tax and spend policies like those listed above have historically helped to reduce inequality by over 25% and poverty by over 50%. This requires, among other measures, the closing of tax havens and loopholes.

Just as the world pivots to address the catastrophic effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic, inequality reduction demands a similar sense of urgency. The price of inaction compounds over time in the form of not just increased inequality but growing frustration and social unrest. Ensuring a more level playing field means overcoming both economic imbalances and entrenched political and power relations. The wealthy need to give up some of their power and privileges and accept that they should pay more in taxes.

While our short-term focus is on flattening the curve and discovering a vaccine, the COVID-19 crisis requires that we fundamentally rethink politics and economics at the global level. To limit the suffering – including when and where the next pandemic strikes – and ensure that people can achieve their full potential and flourish, we need a comprehensive plan to address entrenched inequalities in a post-COVID world.

How Global Public Health Could Revive Multilateralism

In the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, national responses are vital, but in the medium term, international cooperation will be our best weapon. And reforming and reinforcing the institutions and mechanisms that underpin such cooperation will be our best defense against future global threats.

MADRID – As the world struggles to contain COVID-19 and mitigate its impact on our lives and livelihoods, it should be clear to everyone that international cooperation is the only effective way to win the battle. National responses are vital, but in the medium term, multilateralism will be our best weapon in this fight – and our best defense against future global threats.

My country, Spain, is on the front lines of the pandemic. The coronavirus hit us earlier and harder than most other countries. We are mourning thousands of deaths. Our health system has been put to an extreme test. The public is enduring long confinement with exemplary civic duty. And we have had to take unprecedented measures to safeguard our economy.

As governments, our primary responsibility is toward our nationals. But we know that no country will be completely safe until all control the pandemic and, eventually, eradicate it. Our initial international disunion has only strengthened our enemy, moving us further away from our shared goal.

Drawing on some of the lessons we are still learning, we urgently need to devise a more effective approach to global public health that integrates new international, European, and national policies and initiatives.

First, at the international level, we need a more effective framework to prevent, detect, and respond to diseases and pandemics, rooted in reinforced institutions and new mechanisms designed to prevent some of the failures we have witnessed. The new institutional arrangements should be based on a revitalized and reformed World Health Organization, with wider mandates and greater enforcement authority. The WHO ought to have the capacity to design and impose better protocols for preparedness and reaction, compel data sharing, and mobilize whatever resources are needed.

A global health framework with teeth must also be agile enough to cover the whole chain of public-health interventions, from scientific research and early warning to policy formulation, implementation, and evaluation. That’s why, aside from necessary reforms of the WHO’s decision-making process and its Emergency Committee, the potential of other international platforms and organizations to contribute to the global health system we need should not be overlooked.

For example, the G20 and the G7 can help marshal the necessary political will. The World Bank and other regional development banks are uniquely well positioned to mobilize resources toward health-care reform. And organizations like the OECD have the analytical firepower to distill best health policies and practices. Overall, we need to advance a “one health approach” that brings together the environmental, economic, social, and security dimensions of public health.

Second, the European Union should provide a model of preparedness and crisis management that other regions might emulate, by pooling resources and devising new mechanisms for joint action. Besides leading in the establishment of a new and stronger global health framework, the EU can and should improve its own internal coordination. After all, it was sectoral collaboration on coal and steel that gave birth to the EU, the most innovative global governance mechanism that the world has seen. A similar level of ambition is now needed to combat the health challenges we share.

Deeper European integration in this area would yield several significant benefits. The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control should gain greater autonomy and resources. A real European Crisis Management Unit could be established, with the means to ensure a rapid response to an emergency. Systematic stress tests on national health systems should also be conducted to assess EU members states’ resilience against shocks. Like the rigorous stress tests conducted on our financial sectors, the process should allow for shortcomings to be addressed, best practices to be shared, and coordination tools to be developed.

Moreover, the EU should invest in joint databases, medical reserves, and stockpiles. Likewise, it should harmonize protocols and foster scientific collaboration on developing treatments and vaccines. In the immediate term, European countries should cooperate on a coordinated transition strategy to restart the economy without triggering a new outbreak.

Finally, at the domestic level, we all have much to do – as a duty not only to ourselves and our countries’ inhabitants, but also to our neighbors and the international community at large. In Spain, we will establish a commission to assess the state of our health-care system and fix its weaknesses and shortcomings. But, because we know that pandemics affect the world’s most vulnerable people the hardest, we will also reinforce our health diplomacy. Strengthening national health systems requires sharing our experience with other countries and learning from theirs, as well as placing a higher priority on health-sector reforms in our development cooperation.

If we take steps like those proposed here, this pandemic will leave us better prepared for the next one. But we should seek a bigger silver lining. International cooperation on health issues should be extended to other global “public bads” that we have failed to address effectively: climate change, armed conflicts, poverty, rising inequality, international migration, nuclear proliferation, terrorism, and more. The urgency of these challenges may seem less pressing now, but the threats they pose to all of us persist.

In our interconnected world, we need to revive multilateralism by making it more coherent and fit for purpose. That means reinforcing the institutions and mechanisms that work, reforming or eliminating those that don’t, and creating those we need. This crisis reminds us of our fragility and the importance of international unity. It leaves no doubt that we are in this together. And it makes clear why we should view closer cooperation on global public health as a catalyst for the multilateralism we need.

LONDON/CAMBRIDGE – The nations of the developed world have responded to the COVID-19 crisis by supporting their domestic economies and financial systems in bold and unprecedented ways, on a scale that would have been unimaginable three months ago.

In contrast, when the world’s finance ministers and central bank governors convene virtually this week for the semi-annual International Monetary Fund-World Bank meetings, steps will be taken to fortify the international system. But nothing comparable to what countries are doing domestically.

Historians such as Charles Kindleberger have argued convincingly that it was a failure of international cooperation that made the depression of the 1930s “Great.” And even when there has been coordinated action in response to the crises that have occurred since, more often than not it has been taken after a huge human cost.

The Bretton Woods conference on reconstructing the international financial system came after the devastation of a world war. The Brady Plan for resolving the Latin American debt crisis was agreed to only after the region suffered a lost decade.

The 2009 London G20 meeting on the global financial crisis, however, demonstrated the value of early and coordinated action to limit the damage to the global economy, maintain trade, and support fragile emerging markets.

The next wave of the COVID-19 crisis will occur in the developing world. Around 900,000 are likely to die in Asia, and a further 300,000 in Africa, according to grim, but perhaps cautious, estimates from Imperial College London.

While social distancing is the West’s route to suppression of the virus, the developing world’s crowded cities and often overcrowded slums make isolation difficult. Advice on hand-washing means little where there is no access to running water. Without a basic social safety net, choices are narrow and stark: go to work and risk disease, or stay home and starve with your family.

But if the disease is not contained in these places, it will come back – in second, third, and fourth waves – to haunt every part of the world.

Pervasive economic and financial failure in emerging markets also threatens the viability of the supply chains on which all countries depend. Given its magnitude, emerging-market debt threatens the stability of a global financial system that is already dependent on strong central bank support.And with emerging markets accounting for more than half of global GDP, global growth is threatened as well.

Just as the US Federal Reserve and other major central banks have expanded their balance sheets in previously unimaginable ways, the international community needs this week to do, in former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s famous phrase, “whatever it takes” to maintain a functioning global financial system. At a time when the United States is borrowing an extra $2 trillion to meet its needs, it would be tragic if massive austerity was forced on an already-stressed developing world.

First, the IMF, the World Bank, and regional development banks need to be as aggressive as the world’s central banks in expanding their lending. This means recognizing both that the current near-zero interest-rate environment makes it possible to use more leverage than previously, and that there is little point in having reserves if they cannot be utilized now.

The World Bank nearly tripled its lending in 2009. An even more ambitious target may be appropriate now, along with a major increase in subsidized lending at a time when low borrowing rates in rich countries make it much less costly. In addition to relieving debt interest payments, the IMF, with its $150 billion in gold reserves and network of credit lines with central banks, should be prepared to lend up to $1 trillion.

Second, if ever there was a moment to expand the use of the international currency known as Special Drawing Rights (the IMF’s global reserve asset), it is now. If global money is to stay in balance with the domestic monetary expansion in rich countries, an increase in SDRs of well over $1 trillion is urgently needed.

Third, it would be a tragedy and a travesty if stepped-up global financial support for developing countries ended up helping those countries’ creditors rather than their citizens. National debts incurred before the crisis must be at the top of the international financial agenda. We should agree now that once we have clarity on the economic fallout of the crisis, we will pursue the kind of systemic approach required to restore debt sustainability in a number of emerging-market and developing countries, while safeguarding their prospects for attracting new investment.

But the most immediate and largest short-term support can come from waiving upcoming debt payments by the 76 low- and lower-middle-income countries that are supported by the International Development Association.

The current proposal is that creditor countrieswould offer a six- or nine-month standstill on bilateral debt repayment, at a cost of $9-13 billion. But this proposal is constricted both in its time frame and the range of creditors included.

We propose relieving over $35 billion due to official bilateral creditors over this year and next, because the crisis will not be resolved in six months and governments need to be able to plan their spending with some certainty.

Here the role of China, which holds over a quarter of this bilateral debt, will be crucial. China’s decision to be a long-term provider of funds for investment in developing economies has been welcome, and its spending has speeded the development of important infrastructure. Now is the time for China to play a leadership role with other creditors by waiving its debt repayments this year and next.

Nearly 20 years ago, when we both argued the case for debt relief for nearly 40 highly indebted poor countries, almost all the debt was owed to official bilateral or multilateral creditors and little to the private sector. Now, $20 billion – often borrowed at high interest rates – is due by the end of 2021 to private-sector creditors.

As recognized by the Institute for International Finance, which represents private-sector creditors to emerging markets, the private sector has to take its share of the pain. It would be unconscionable if all the money flowing from our multilateral institutions to help the poorest countries was used not for health care or anti-poverty measures, but simply for paying private creditors, especially those like the large American banks that are continuing to pay dividends at a time of crisis. The ministers and governors convening this week should join their authority with that of the IMF and the World Bank to mobilize the private sector around a voluntary plan for addressing these debts.

Just as the pandemic can be contained most effectively and least expensively with bold early measures, the lesson from the past is that international recessions and their consequent human costs are best addressed quickly and boldly. We must act fast and act together.