The Pandemic’s Gender Imperative

Given that the COVID-19 crisis affects men and women in different ways, measures to resolve it must take gender into account. For women and girls, vulnerabilities in the home, on the front lines of health care, and in the labor market must be addressed.

Will the Pandemic Set Women Back?

By sapping demand for garments and other goods produced in export-oriented developing and emerging economies, the COVID-19 pandemic poses an acute threat to women workers and progress toward greater gender equality. In addressing the economic fallout of the public-health crisis, policymakers must tailor their response accordingly.

PRINCETON/TORONTO – In April, the International Labor Organization predicted that 195 million workers worldwide would “suffer severely” in the second quarter of this year, owing to the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. And markets remain shaky, raising fears of a recession more severe and prolonged than that following the 2008 financial crisis. The stakes are high for everyone, but particularly for women – and especially for women in developing and emerging economies.

A recession (or even depression) would cause more than just economic losses. The experience of the post-2008 period suggests that women’s advances will be rolled back substantially, even among those already doing low-income work. In that case, the gains will be difficult, if not impossible, to win back.

The COVID-19 crisis, like the 2008 crisis, has revealed features of globalization that many take for granted in normal times. When advanced economies like the United States contract sharply, their consumers cut back on spending, and demand for goods from export-oriented countries plummets. Owing to the pandemic, the low-wage global garment industry is facing what some manufacturers describe as an “apocalyptic” situation.

Women make up over three-quarters of the global garment workforce, and thus have the most to lose from the downturn. Most have long been subject to poor working conditions, which makes their situation even more precarious. Since the 1970s, clothing manufacturers in developed countries have offshored and outsourced their productive capacity to developing countries with the lowest wages and, by proxy, the weakest labor standards. Along this global assembly line, employment is typically temporary, job-based, sub-contracted, and insecure.

Nonetheless, while there is rampant exploitation in the industry, there are also opportunities for women. For many employed in the garment sector, a job in a clothing factory provides an entry point to participation in the formal economy – steady work for a stable wage with tangible benefits. Work in the sector comes with the promise of independence, skills development, mobility, and a better quality of life.

The COVID-19 crisis endangers not only these women’s jobs, but also the potential for gender empowerment more broadly. In a recent study of garment-sector workers in Kenya, Lesotho, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Bangladesh, we found that access to waged employment can broadly advance women’s prospects in highly gender-unequal societies. The data show that garment-sector employment for women has translated into broader improvements in gender dynamics. Among the countries considered, the most significant shifts have occurred in factories where there have been specific interventions to improve workplace health and safety, such as training in manager-employee communication.

The ripple effects from women’s wage earning in manufacturing are evident in household gender relations. Female study participants demonstrated an increased ability to leverage the material resources that they contribute to engage male partners more effectively in decisions about spending and other household matters. Study participants also reported increased participation by men in domestic and caretaking labor typically carried out entirely by women. The sharing of household work has helped to reduce the “time poverty” that study participants would otherwise experience as a result of their dual roles as wage earners and caretakers. And this, in turn, has improved both their physical and emotional wellbeing.

In limited but meaningful ways, these changes have mitigated key sources of household financial precarity and conflict, as well as enhanced women’s self-respect and sense of agency. However, with the spread of COVID-19, lockdown measures are leading to a reported global surge in domestic violence – much of it triggered by stress, financial difficulties, and alcohol consumption. And this problem is particularly acute in cases where women who previously provided a significant share of the household’s income have been prevented from doing so because they can no longer go to work.

Given these heightened risks, policymakers, central bankers, and economists scrambling to cushion the financial impact of the public-health crisis must do more to consider the stakes for women wage earners in developing and emerging economies. Safeguarding the gains these women have made will require investments and policies not only to address widespread unemployment, but also to bolster programs to facilitate gender advancement.

In other words, the COVID-19 response cannot be gender-neutral. To account for the unique conditions experienced by women workers, policymakers must focus on wage-replacement benefits, women’s shelters (which should be categorized as essential services), emergency childcare provisions, access to proper feminine hygiene, and public-health messaging that can reach marginalized women who lack digital or cellular connectivity. At the very least, we must defend the progress that women have made through generations of work toward gender equality and empowerment.

Will COVID-19 Widen the Gender Justice Gap?

Globally, women have only three-quarters of the legal rights afforded to men, with the worst inequalities relating to family relationships, employment, control of economic assets, and violence. Ensuring that the current pandemic does not deepen these disparities is therefore crucial.

WASHINGTON, DC – Worldwide, an estimated 1.5 billion people face legal problems they cannot resolve, while 4.5 billion – particularly women, the poor, and other vulnerable people – are excluded from the protections and opportunities that the law provides.

True, the news is not all bad. United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 16 aims to “provide access to justice for all,” while multidimensional poverty measures increasingly consider justice-related indicators. Moreover, enhanced data-collection methods and more readily available global and national statistics have improved the measurement of justice gaps and filled critical data voids.

But COVID-19 is creating further obstacles to equal access to justice, especially for women. Pandemic responses are likely to be heavily gendered, meaning that migrant, disabled, and indigenous women are doubly disadvantaged. Ensuring that the current crisis does not widen existing gender-based legal disparities is therefore crucial.

Those disparities were already pronounced before the pandemic, with many women facing an uphill battle to gain access to justice. Despite numerous legal reforms, women globally have only three-quarters of the legal rights afforded to men, with the worst inequalities relating to family relationships, employment, control of economic assets, and violence.

Women do not necessarily experience more legal problems than men. But they tend to face specific problems with issues like alimony and child support, sexual violence, lack of legal identity, and access to social safety nets. Taken together, the socioeconomic impact of such problems is enormous.

Furthermore, women frequently lack the financial resources and social networks to navigate justice systems. Social norms, which often are more restrictive than laws, may prevent them from taking legal action. And even when they do act, gender-biased public officials may undermine them. And women who must already balance family care with formal or informal jobs may lack the time to go to court.

Courts are not the only avenue for seeking justice, but they are an important one, and COVID-19 has exposed their weaknesses. Courts have traditionally been slow to adopt technology, rely too much on in-person appearances, and have struggled to make their services accessible to people lacking lawyers or other legal assistance. Understanding their specialized language is difficult without a law degree, while the sort of client-centered approaches common in other public services remain rare.

In response to the pandemic, courts are changing their practices in ways that may improve access, including by embracing technology to share information and conduct transactions such as submitting petitions and requesting protection orders. Remote hearings using phones and video have become a new normal, while some court services can be provided via email and text message. But while the new embrace of technology should be welcomed, vulnerable people, including women, are at risk of being left behind.

Courts have also adopted a triage approach during the crisis, for example by postponing non-emergency cases and extending existing judicial orders. Women have benefited from blanket extensions of protection orders and child-custody decisions. More generally, judicial triage points to how cases can be resolved most efficiently in the longer term.

The OECD and the United Kingdom have already launched initiatives to monitor new court service methods and capture the gains. Such data are increasingly seen as necessary to underpin judicial reforms.

And significant, lasting reforms may well be needed, given the additional threats posed by the pandemic and its economic fallout. For starters, worsening financial, family, and health problems will likely lead to an upsurge in violence against women. Germany, Spain, the UK, the United States, and Canada are already reporting rising levels of domestic violence and requests for emergency shelter. But lockdowns and other crisis measures may have cut off the usual routes for addressing violence.

Likewise, recession and unemployment are liable to reduce men’s ability to pay alimony and child support, requiring courts to enforce or amend earlier decisions. And women may find it difficult to access social-protection payments and other crisis-related benefits if they lack legal forms of identification, are excluded from public-information initiatives, or lack the financial resources to seek legal help.

Women’s financial constraints will become increasingly salient, because the pandemic is also likely to exacerbate existing economic gender gaps, further limiting women’s access to justice. For example, those whose husbands die of COVID-19 may lose access to sources of wealth such as land and savings. Without special legal protections to prevent economic gaps from widening, loss of assets will make it harder for women to navigate justice systems or afford assistance. In many countries, the poor rely disproportionately on legal aid services, which have been shown to have positive social and economic effects on women and their households. But the sharp economic downturn is likely to threaten this resource as well.

Finally, the crisis may trigger a backlash on social norms, undermining women’s ability to challenge unfair laws and practices. It could also lead to weaker enforcement of reforms of family and employment law that have benefited women.

There are two ways to mitigate these risks. First, the pandemic must not be permitted to widen the gender justice gap. This will require assessing whether judicial responses to the pandemic may have planned or unintended negative consequences for women. And we need to view gender in the context of other overlapping dimensions of disadvantage such as poverty, ethnicity, disability, language, and location.

Second, the crisis gives us an opportunity to add to our growing knowledge of what works in improving women’s access to justice. This calls for monitoring and evaluating new initiatives and collecting data. Above all, measures that help to close the gender justice gap should be made permanent and scaled as appropriate, rather than being regarded as temporary and reversible.

Winning the War Against Maternal and Child Deaths

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the world was not on track to deliver on its promise – included in Sustainable Development Goal 3 – to end preventable maternal and child mortality by 2030. And now the pandemic is jeopardizing precious but fragile gains.

GENEVA/LONDON/NEW YORK – As the world focuses its attention on winning the battle against COVID-19, we must not forget that we are still fighting a war against preventable child and maternal deaths – a war that world leaders pledged to win by 2030. The international community must recommit to that promise and deliver on it this decade.

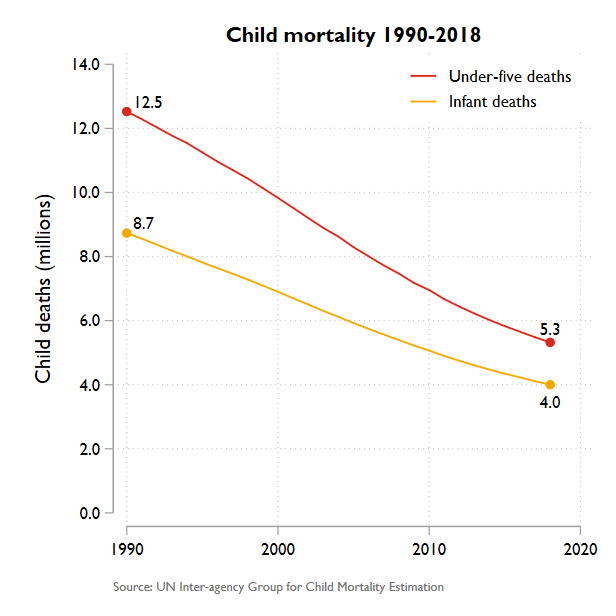

Child survival is perhaps the greatest untold success story in the recent history of international development. Since the early 1990s, the mortality rate for children under age five has plunged by nearly 60%. And the annual rate of decline has accelerated since 2000, saving millions of lives. Maternal mortality has also fallen rapidly – by nearly 40% over the last 20 years.

These gains are largely the result of efforts to extend the reach of health systems in the world’s poorest countries. Primary health care has been the catalyst for some of the most impressive gains. Countries such as Bangladesh and Ethiopia have achieved astonishing progress by training and deploying health workers where they can be most effective – namely, in the communities they serve.

International cooperation has been another powerful driver of change. Aid provided through Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance since 2000 has enabled over 760 million people to be immunized against deadly diseases, saving more than 13 million lives.

Despite this progress, children and their mothers are still dying at appalling rates. Over five million young lives are still being lost every year – almost half in the first month of life – to preventable or treatable diseases like pneumonia, malaria, and diarrhea. More than 800 women and adolescent girls die every day from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, owing largely to a lack of reproductive health care.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the world was not on track to deliver on its promise – included in Sustainable Development Goal 3 – to end preventable maternal and child mortality by 2030. If progress over the next decade mirrors the last, over three million children will still be dying annually in 2030. Maternal survival goals will also be missed by a wide margin.

The danger now is that COVID-19 will widen the gap between the SDG promise and reality. Supply-chain disruptions, intensifying financial pressures, and the diversion of health workers and resources are already undermining service delivery in vulnerable areas. Gavi reports delays on “14 Gavi-supported immunization campaigns,” as well as “four national vaccine introductions,” leaving over 13 million people – many of them children – without vaccine protection.

Meanwhile, lockdown policies and fear of infection are deterring people from seeking other kinds of health care. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine estimate that a 15% reduction in the use of routine health services over a six-month period could lead to an additional 253,000 child deaths. Another research team at the Guttmacher Institute estimates that even a modest decline of 10% in coverage of pregnancy-related and neonatal health care would result in an additional 28,000 maternal deaths and 168,000 newborn deaths.

We have seen this story play out before. During the 2014-16 Ebola crisis in West Africa, the breakdown in routine service delivery caused a catastrophic surge in child deaths from malaria and other diseases, as well as an increase in maternal mortality and stillbirth.

Like Ebola, COVID-19 demands the world’s attention – and cooperation. Without a vaccine, there is no exit from the pandemic. That is why the development and equitable distribution of a vaccine is so critical. International cooperation to strengthen health systems and deliver the tests, protective equipment, and medical supplies needed to save lives remains a first-order priority.

But we must not allow a new health crisis, however deadly, to increase the toll of old killers on the world’s most disadvantaged children and women. Avoiding that outcome will require a four-pronged approach.

First, governments and aid donors must defend hard-won gains in child and maternal health by protecting budgets for community health services, including maternal health care and immunization. Next month’s donors’ meeting to decide on Gavi’s funding for 2021-25 is critical. By heeding Gavi’s call for $7.4 billion in funds, donors would enable the organization to immunize an additional 300 million children in developing countries over this period – saving up to eight million lives. There is no more cost-effective health investment.

Second, efforts to build more resilient health systems should be strengthened, with a focus on addressing the weaknesses that COVID-19 has exposed. For example, many of the world’s poorest countries lack medical oxygen, which is essential for treating not only COVID-19, but also childhood pneumonia – which kills 800,000 under-five children each year – as well as malaria, sepsis, and newborn respiratory problems.

Third, it is time to abandon the false notion that universal health coverage is an unaffordable luxury. What is unaffordable is the inequality, suffering, and inefficiency that comes with financing health services through user charges imposed on people too poor to pay. With poverty set to rise, the elimination of these charges and strengthening of publicly financed health systems is more urgent than ever. In fact, universal health coverage is included in the same SDG as preventable maternal and child deaths, underscoring their interconnectedness.

Finally, as financial pressures on health systems mount, we must explore every avenue for resource mobilization. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank have secured a commitment from the G20 countries to suspend debt repayment from the poorest countries. Surely this is an opportunity to convert money earmarked for debt servicing into an investment fund for child and maternal health.

COVID-19 is a devastating reminder of our shared vulnerability. But we are all united by the shared values reflected in our pledge to end preventable child and maternal deaths. As we fight the pandemic, we must hold to that pledge and fulfill the promise made to the children and women whose lives are at stake.

Sexual and Reproductive Health During the Pandemic

COVID-19 has not stopped people from having sex and reproducing, despite strained health-care systems. The crisis is an opportunity for policymakers to support initiatives that give women and girls more power over their immediate needs and improve access to critical services in the long term.

NEW YORK – The COVID-19 crisis has disrupted almost every aspect of life, but not sex. Both wanted and unwanted intimacy occurs during a pandemic. With reduced mobility and less access to clinics and hospitals, ensuring quality and timely reproductive health care is more important than ever.

The virus has revealed stark inequities in medicine – and not only in emergency care. Even before COVID-19, adolescent girls, migrants, minorities, people with disabilities, and LGBTQI+ people faced discrimination in doctors’ waiting rooms. The crisis is an opportunity for policymakers to support initiatives that give women and girls more power over their immediate needs and improve access to critical services in the long term.

The first priority is to make oral contraceptives available over the counter. This will increase safety, access, and use. In most places, a prescription is required, which prevents women from being fully in control of their bodies. It also may interfere with a patient’s access to care free of abuse or privacy violations. This is especially true for teenagers, gender non-conforming people, domestic violence victims, and others who fear discrimination or disrespect in clinical settings.

The benefits of making contraceptives more widely available far outweigh the low risks. Evidence shows that women and gender non-conforming people can screen themselves for counter-indications using simple checklists that accompany medication. Permitting people to get a year’s supply, so they can self-administer injectables like Depo-Provera would benefit those in violent situations and others who may struggle to access healthcare. Eliminating third-party authorization requirements and lowering costs for contraceptives would help, too.

Second, we must make abortion more accessible. Regressive policies and recent lockdowns have made in-clinic abortions less available, even though it is an essential medical procedure. Policymakers can and should take simple steps to eliminate unnecessary obstacles to abortion with pills, which would expand women’s freedom and reduce clinic visits.

Medical abortions are safe and effective. Millions of women self-terminate pregnancies every year, whether using a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, or misoprostol alone. There is no need for an office visit. People seeking abortions can assess whether they are eligible, follow instructions on correct dosages, and determine if the abortion is successful. All they need is accurate information, medication, and access to back-up health care if necessary.

The best way to increase abortion access is to make mifepristone and misoprostol available over the counter. At a minimum, policymakers should make them easier to attain through telemedicine. This is viable and safe as long as consumers are educated about what to expect and can receive post-abortion care without judgment, stigma, or fear of prosecution. People who self-manage their abortions should not be harassed or penalized.

Quality maternal care also is crucial for women in the coronavirus era. Pregnant women face the same stresses as everyone in a pandemic. They face possible job insecurity, loss of income, health coverage changes, and threats to their own health. And then there are unique concerns about the health of their fetuses and newborns.

In many places, overburdened health-care systems can’t provide pregnant women with the level of maternal care they expected – and received – before the pandemic. To address this gap, practitioners should help pregnant women practice greater self-care by providing the right tools and information, such as telemedicine, online education, home visits by midwives and other providers, psychosocial support, and ample screening.

These measures will ensure that pregnant women can better monitor their own health, manage common symptoms, identify signs of complications, and know when to seek care. And when they do, they must be able to travel to health-care facilities, even where lockdowns are enforced. This means ensuring emergency transport and personal protective equipment for pregnant women and those who accompany them.

Moreover, policymakers should expand initiatives that de-medicalize birth. Attended home births for low-risk pregnancies, guaranteed presence of midwives, dedicated birthing facilities linked to tertiary care, and home visits for antenatal care help ensure safer deliveries for mothers and providers alike. Many countries have emphasized institutional care, even though de-medicalizing childbirth is beneficial in the best of times, not just in a crisis.

We must avoid enacting knee-jerk measures. It would be regressive to restrict or ban partners or doulas from labor, separate infants from mothers who have, or are suspected to have, COVID-19, or interfere with early skin-to-skin contact, including breastfeeding. The World Health Organization has urged providers to refrain from such measures while caring for pregnant women, parents, and infants. This is critical to prevent an increase in obstetric violence or worse outcomes for women and their newborns.

Governments that do not eliminate barriers to care risk fractured health systems that cannot tend to everyone’s needs. In the long term, investments in self-empowerment will strengthen health systems and the quality of care. With education and support, people can manage their sexual and reproductive health-care needs. Policymakers need to give them the power and tools to do so.

Why Women Make Better Crisis Leaders

While many factors are shaping outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, leadership is undoubtedly one of the most important. It should surprise no one that, by and large, it is the leaders who have already had to prove themselves who are the most effective.

LONDON – While many countries continue to grapple with escalating COVID-19 outbreaks, two have declared theirs effectively over: New Zealand and Iceland. It is no coincidence that both countries’ governments are led by women.

New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and her Icelandic counterpart Katrín Jakobsdóttir have both received considerable – and well-deserved – praise for their leadership during the COVID-19 crisis. But they are not alone: of the top ten best-performing countries (in terms of testing and mortality), four – Estonia, Iceland, New Zealand, and Taiwan – have woman leaders. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen have also been commended for their pandemic leadership.

Women account for less than 7% of the world’s leaders, so the fact that so many have distinguished themselves during the COVID-19 crisis is noteworthy. But that’s not all. Some of the worst-performing countries are led by unapologetically old-fashioned “men’s men.” Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s entire persona channels a retrograde masculinity and a patriarchal view of women. Accordingly, he has called the virus a “measly cold,” boasting that he “wouldn’t feel anything” if infected.

In the United Kingdom – which has recorded the most COVID-19 deaths in Europe – Prime Minister Boris Johnson also has a history of sexist comments. Like Bolsonaro, Johnson’s first instinct was to minimize the threat COVID-19 poses, though he changed his tune after being infected and ending up in an intensive-care unit.

It’s the same story with US President Donald Trump. A leader who came to power gloating about powerful men’s ability to assault women sexually – which he and his supporters dismissed as “locker-room banter” – Trump has often worn his misogyny like a badge of honor. He, too, has consistently downplayed the COVID-19 crisis, focusing instead on “making China pay” for allowing the virus to spread beyond its borders.

Just as leaning into masculine stereotypes seems to correlate with poor pandemic responses, many observers seem to believe that woman leaders’ success may be rooted in their traditionally “feminine” qualities, such as empathy, compassion, and willingness to collaborate. Forbes called Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg’s televised address to her country’s children an example of the “simple, humane innovations” that are possible under female leadership.

This reading is outdated, reductive, and simply wrong. Trump and his ilk may act tough, but ultimately their leadership is an incompetent charade of bluster, vacillation, and self-aggrandizement. High-performing female leaders, by contrast, have been resolute, assessed the evidence, heeded expert advice, and acted decisively.

Following the mantra “go hard and go early,” Ardern imposed a strict lockdown four days before New Zealand’s first COVID-19 death. Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen introduced more than a hundred public-health measures in January – when the World Health Organization was still casting doubt on the possibility of human-to-human transmission.

If traditionally “feminine” traits don’t explain female leaders’ strong performance in times of crisis, what does? The answer may be related to the path women take to power, which is generally more demanding than that faced by men. In particular, it may be linked to the “glass cliff” phenomenon, whereby women are more likely than men to be appointed to leadership positions that are “risky and precarious.”

Research into the glass cliff began with the finding that, before appointing men to their boards, companies in the Financial Times Stock Exchange 100 Index typically experienced stable share prices. Before appointing a woman, however, those same companies often experienced five months of poor share-price performance. Another study found that companies listed on the UK stock exchange tended to increase gender diversity on their boards after experiencing big losses.

A similar tendency can be seen in politics. Margaret Thatcher became leader of a Conservative Party in crisis, and prime minister after a “winter of discontent.” Archival analysis of the 2005 UK general election found that female Conservative Party candidates tended to contest seats that would be significantly more difficult to win (judged according to their rival’s performance in the previous election).

Ardern also got her break by being thrust onto a glass cliff: she became the leader of New Zealand’s Labour Party in 2017 after poor polling forced her predecessor to resign. A mere two months later, she became the country’s youngest prime minister in 150 years.

According to the researchers, the glass cliff may appear because organizations are more willing to challenge the status quo when the status quo isn’t working. The visible difference of having a woman in charge could also reassure stakeholders that change is happening. As for the women, they may be more likely to accept leadership positions in times of crisis because they have fewer opportunities to reach the top. They can’t simply wait for an easier post to open up.

Regardless of why it happens, the fact is that by the time a woman reaches the heights of corporate or political power, she is likely to have overcome massive hurdles. With men, that is possible, but far from guaranteed. Johnson (who was fired from multiple jobs for lying) and Trump (with his meticulously documented history of business failures, including several bankruptcies) never seem to run out of second chances. These leaders’ paths to power are characterized more by plush cushions than glass cliffs – and it shows.

While many factors are shaping outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, leadership is undoubtedly one of the most important. It should surprise no one that, by and large, it is the leaders who have already had to prove themselves who are the most effective. That very often means they are women.

STOCKHOLM/MADRID – Regardless of where one looks, it is women who bear most of the responsibility for holding societies together, be it at home, in health care, at school, or in caring for the elderly. In many countries, women perform these tasks without pay. Yet even when the work is carried out by professionals, those professions tend to be dominated by women, and they tend to pay less than male-dominated professions.

The COVID-19 crisis has thrown these gender-based differences into even sharper relief. Regional frameworks, multilateral organizations, and international financial institutions must recognize that women will play a critical role in resolving the crisis, and that measures to address the pandemic and its economic fallout should include a gender perspective.

We see three areas where women and girls are particularly at risk and in need of stronger protections in the current crisis.

First, experience shows that domestic, sexual, and gender-based violence increases during crises and disasters. It happened during the 2014-16 Ebola and 2015-16 Zika epidemics, and it appears to be happening now. Under conditions of quarantine or stay-at-home measures, women and children who live with violent and controlling men are exposed to considerably greater danger.

The need to support these women and children will only increase when the crisis is over and people are free to move around again. We must ensure that women’s shelters and other forms of assistance are maintained and strengthened accordingly. Governments and civil-society groups must provide more resources such as emergency housing and telephone helplines, perhaps leveraging mobile technologies in innovative new ways, as is happening in so many other domains.

Second, the majority of those on the front lines of the pandemic are women, because women make up 70% of all health and social-services staff globally. We urgently need to empower these women, starting by providing more resources to those who also assume primary responsibility for household work. Increasingly, that could include caring for infected family members, which will subject these women to even greater risk.

Women also account for the majority of the world’s older population – particularly those over 80 – and thus a majority of potential patients. Yet they tend to have less access to health services than men do. Worse, in several countries that experienced previous epidemics, the provision of sexual- and reproductive-health services – including prenatal and maternal care and access to contraceptives and safe abortions – was reduced as soon as resources needed to be reallocated for the crisis. Such defunding has grave consequences for women and girls, and must be prevented at all costs.

Finally, women are particularly vulnerable economically. Globally, women’s personal finances are weaker than men’s, and their position in the labor market is less secure. Moreover, women are more likely to be single parents who will be hit harder by the economic downturn that is now in full swing.

Given these differences, it is critical that economic crisis-response measures account for women’s unique situation. Particularly in conflict zones and other areas where gender equality receives short shrift, women and girls risk being excluded from decision-making processes, and potentially left behind altogether.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women, where the international community adopted the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. We are calling on all governments to recommit to the principle that women have the same right to participate in decision-making as men do – that their perspectives must be accounted for.

To that end, policymakers at all levels need to listen to and engage with women’s rights organizations when formulating responses to this crisis, and when preparing for the next one. The guiding question always should be: Are women and men affected differently by this issue, and, if so, how can we achieve fairer outcomes?

We must ensure that girls have just as much time to study as boys do and do not bear full responsibility for the care of siblings and parents. We also must learn the right lessons from the COVID-19 crisis, which demands that we take a hard look at how we value and pay for women’s contributions to health care, social services, and the economy. How can we ensure that women are not excluded from important political processes now and in the future?

Today, all countries are facing the same crisis, and none will prevail over COVID-19 by acting alone. Given that we share the same future, all of us must work to ensure that it is one built on solidarity and partnership. Governments and the UN must show leadership. We know that gender-equal societies are more prosperous and sustainable than those with deep disparities. The world’s decision-makers have an opportunity to make gender equality a top priority. We urge them to rise to the occasion.

This commentary is co-signed by Shirley Ayorkor Botchwey, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration, Ghana; Kamina Johnson-Smith, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Foreign Trade, Jamaica; Kang Kyung-wha, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Korea; Retno Marsudi, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Indonesia; Grace Naledi Mandisa Pandor, Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, South Africa; Marise Payne, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Australia; Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, Executive Director of UN Women; and Ine Marie Eriksen Søreide, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Norway.