America’s Republicans Are Killing Their Voters

Despite mounting evidence that vaccination leads to lower COVID-19 mortality rates, many in the US remain skeptical, if not downright hostile. An analysis of the data that isolates the causal effect of voting patterns clearly shows the heightened danger Republicans face.

That Old Time Anti-Vaxx Feeling

The best single predictor of vaccine uptake per US state is not political affiliation, but the share of the population that believes the human race has always existed. Such findings do not bode well for the global effort to boost vaccination rates.

BRUSSELS – Vaccination is the best protection against COVID-19, and the evidence for that is overwhelming. While protection against infection or transmission is not guaranteed – especially with the Delta variant raging – getting vaccinated substantially reduces the risk of severe illness, hospitalization, and death from the coronavirus. Widespread vaccination is thus the key to enabling responsible governments to relax public-health restrictions, thereby allowing the economic recovery to continue. But this seems increasingly to be out of reach.

Researchers estimate that 70-85% of the population needs to be vaccinated (or otherwise immune to COVID-19) to end the pandemic. Yet even in Israel, which was leading the world in its vaccination drive at the beginning of 2021, the share of the population that has been vaccinated has stalled at just over 60%. In the United States, only about half the population is now protected, and vaccination rates have plummeted from 3.2 million doses per day in April to fewer than 700,000 doses per day as of early August.

The US case is particularly interesting, because the country-wide average obscures large differences among socio-economic groups and across states. Whereas over 63% of people in Massachusetts and Maine are fully vaccinated, only 34% of people in Mississippi and Alabama are. Across towns and counties, the disparities are even larger.

This is less a problem of access than of acceptance. It has been widely observed that, at least in the US, the willingness to be vaccinated is correlated with political affiliation. Polls show that only around 54% of Republican adults have been vaccinated, compared to 86% of Democrats. In counties that voted for Donald Trump, a Republican, in the 2020 presidential election, vaccination rates are more than ten percentage points lower than in counties that voted for Joe Biden, a Democrat.

But while the statistical link between political affiliation and vaccine hesitancy is strong, correlation does not equal causation. Moreover, anti-vaccine sentiment is nothing new: the NoVax movement existed long before the COVID-19 pandemic. The question, then, is whether people are refusing the COVID-19 vaccine merely because of their political beliefs, or whether those political beliefs and their stance on the vaccine reflect other, deeper factors.

A look at people’s broader attitudes toward science and trust in the establishment (scientific and otherwise) could help us to find the answer. One useful indicator here is the acceptance of evolution. Surveys have found repeatedly that a substantial minority of Americans reject the scientific consensus that humans are the product of a long process of natural selection.

Belief in evolution is strongly linked to acceptance of vaccination. Indeed, the best single predictor of vaccine uptake per US state is the share of the population that believes the human race has always existed.

Interestingly, religious beliefs do not seem to be decisive here. The link between vaccine uptake and the prevalence of the belief that divine intervention steered evolution is rather weak. Furthermore, political partisanship, as measured by voting patterns in the 2020 presidential election, loses its predictive power over vaccine uptake after one accounts for belief in evolution.

The implication is that attitudes toward vaccination are rooted not in party allegiance, but in a latent mistrust of science. This may reflect how democracy works more broadly. As Christopher H. Achen and Larry M. Bartels argue in their 2017 book, Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government, it is not that political parties present their programs, and rational voters choose which to support; instead, parties represent existing identity groups.

In the US, the Republican Party has positioned itself so that it captures the segment of Americans who do not accept science if its results collide with their worldview. This type of person does not believe in evolution (roughly one-quarter of the population, on average) and tends to reject COVID-19 vaccines. But the GOP is not necessarily responsible for those stances. So, contrary to Jeffrey Frankel’s recent assertion, America’s Republicans probably cannot be said to be “killing their voters.”

In a sense, this is bad news. If people’s decision not to get vaccinated is based on fundamental beliefs, it will be much more difficult to change than if it was based on political partisanship or health concerns. Disseminating more factual information – more studies, more statistics – will not make a difference. After all, evolution has been taught in schools for generations.

Financial incentives, like lotteries, might sway some of the doubters. But a substantial community of hardcore anti-vaxxers is likely to remain – and not only in the US. Compulsory vaccination elsewhere, such as in France, is also being met with strong resistance. As the Delta variant fuels new COVID-19 outbreaks, governments in countries with a strong anti-vaxx movement have few good options left.

A Dangerous New Variant of Populism

Although populist governments have been further discredited by poor performances in the face of COVID-19, a new strain of the same politics is already taking shape. Anti-vaxxers and other conspiracy theorists are finding common cause with voters who are worried about the implications of climate policies.

LONDON – Most of the “geopolitical” threats, real or confected, that capture headlines in the West nowadays are exogenous – emanating from China, Russia, Iran, and so forth. But others lie within the world’s democracies. Among these are the US Republican Party’s embrace of Trumpian authoritarianism, which is eroding the country’s democracy, and the possibility that new unanticipated variants of populism will take hold around the world.

One new variant of populism might involve hostility toward both costly green policies and vaccination against COVID-19. And it would be driven by a combination of genuine concerns about pocketbook issues and the kinds of conspiratorial lunacy that thrive on the internet.

Anti-green populism is particularly likely to flourish in the more fossil fuel-dependent economies of Central and Eastern Europe, in response to the European Union’s new strategy for reducing greenhouse gases by 55% by 2030. Indeed, the so-called Fit for 55 plan would seem to call for the wholesale remodeling of these economies.

Consider Poland, which generates 70% of its energy from coal and receives additional supplies through a gas pipeline from Russia. Coal is especially abundant in southern Poland, where it is used to fuel giant power stations that provide industry with cheap electricity.

If it is to meet EU emissions targets, Poland is going to have to decarbonize more extensively and rapidly than anyone else. The government recently set an ambitious goal of reducing the proportion of coal in the country’s energy mix from 70% to 11% by 2040. But that will have massive implications for mining, which employs some 100,000 heavily unionized and politically influential workers.

Moreover, with little wind or sunshine in winter, Poland is ill suited for renewable-energy deployment. Instead, it has set its sights on “solutions” like nuclear power and the “Baltic Pipe” gas pipeline – subsidized by the European Commission to the tune of €215 million ($251 million) – to import gas from Norway via Denmark.

But neither of these options has gone down well in Germany. If Poland’s efforts to align with EU policy put it at loggerheads with key neighbors and trade partners, it will be damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t. The conditions are set for a thriving anti-green populism.

Yet this populist threat is hardly limited to Central and Eastern Europe. Opposition to climate action could just as easily spread to Europe’s more established democracies if costly items like air source heat pumps and smart meters are rendered technologically redundant, or if vehicles with internal combustion engines are forced off the road by government fiat.

In fact, France was briefly the epicenter of an anti-green backlash in Europe, with the rambunctious giletsjaunes (yellow vest) protests that began in 2018. Angry citizens who rely on cars to get around their country districts eventually forced President Emmanuel Macron to rescind a new tax on diesel fuel. They had a point, considering that the infrastructure for more expensive electric vehicles simply does not exist in France (or anywhere else).

More recently, a significant share of this cohort seems to have joined with militant anti-vaxxers (many of them on the far right) who have adopted various libertarian poses propagated on the internet. This confluence of grievance may have traction, especially as more conventional populist movements have begun to take a battering, notably in Hungary, Poland, Slovenia, and elsewhere. People have grown weary of authoritarianism, corruption, and divisiveness during the pandemic – a crisis that was grossly mishandled by populist governments, in particular. The likes of Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán are the elite, not some anti-systemic opposition to it.

Opposition to vaccination is as old as inoculation itself. The English city of Leicester used to be a hotbed of it. In 1885, 100,000 people there attended an anti-vaccination rally, complete with a child’s coffin and an effigy of Edward Jenner, the pioneer of smallpox vaccination. Such movements were often based on a fusion of fundamentalist Christianity (which opposed interference in God’s work) and suspicion of powers being arrogated by the modern state, which made vaccination mandatory for infants or children entering school.

The only unique contribution of our current age is the role of social media in amplifying the views of crank medics and scientists, as happened after The Lancet published (and then retracted) Andrew Wakefield’s false claims that there is a link between the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine and autism.

Nowadays, any online search of vaccines immediately reveals a disproportionate number of anti-vaccination sites, as well as pernicious guff claiming that the barring of unvaccinated youth from nightclubs is akin to Jews being sent to Auschwitz. Versions of that analogy have long appeared in the British Daily Telegraph, courtesy of its dogmatically libertarian commentators, who have made common cause with the likes of the Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), Italy’s homegrown fascist movement. Any enemy of the EU is their best friend by default. Although the overwhelming majority of Italians support the government’s green pass initiative, the Fratelli’s leader, Giorgia Meloni, loudly does not.

In the homeland of Louis Pasteur, such militants are particularly exercised by the government’s vaccine-passport rules, which exclude the unvaccinated from concerts, cinemas, museums, swimming pools, theaters, and restaurants where 50 people or more are gathered. More trouble may ensue if nurses (only 50-58% of whom are vaccinated) are prevented from working until they receive two doses; or if railway workers raise objections about having to enforce vaccine-passport rules on local and commuter trains. No job should involve the risk of being headbutted or punched in the face.

It was perhaps inevitable that the parasitic populist right would latch onto these issues. Although Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Rally party has typically hedged her bets, her former right-hand man, Florian Philipott, was very vocal at the biggest of the many anti-vaccine rallies in July. These are growing in size by the month, with 200,000 attending the first one in August. This “movement” flourishes among the semi-educated in small towns and in cities like Marseille, where obdurate pastis guzzlers and religious immigrant communities also contribute to its ranks.

However, it is worth stressing that 62% of the silent majority in France supports vaccine passports, and 70% want all hospital and care-home workers to be fully vaccinated. That is probably why Macron has stuck to his guns: he hopes that rationality will prevail and that any increase in economic activity will benefit his campaign in 2022. Let’s hope he is right.

Still, one can see the outlines of an emerging political fusion between irrationality and pocketbook issues. As anti-vaxxers and anti-greens join forces, any number of stray populist demagogues might seek to lead such a movement. That underscores the importance of UN initiatives such as Team Halo, which has brought together scientists to publicize the importance of vaccines, especially on social media platforms.

On Liberty, Conspiracy, and Vaccination

Now that vaccine hesitancy has emerged as a major threat to achieving herd immunity, public authorities might be tempted to crack down on the conspiracy theories that are fueling it. But before they do, they should revisit John Stuart Mill's famous defense of free speech.

PARIS – Although countries like Israel, the United Kingdom, and the United States have done particularly well getting COVID-19 vaccines into arms as fast as possible, vaccine hesitancy remains a serious hurdle. In the US, it has already derailed President Joe Biden’s goal of administering at least one vaccine dose to 70% of the US population by July 4.

In a CNN poll in April, about 26% of US respondents said they do not intend to get vaccinated at all. That is a big problem, given that near-universal vaccination is the only reliable way to end the pandemic. Assuming, for example, that COVID-19 variants as contagious as measles become dominant, achieving herd immunity could require that 94% of the population is immune.

In these circumstances, policymakers might be tempted to try to suppress vaccine hesitancy – much of it fueled by conspiracy theories. To believers, the real danger is not COVID-19, but that Bill Gates is using vaccines to implant microchips in our brains.

But aren’t conspiracy theories just another form of free speech? In his classic defense of that principle, On Liberty, John Stuart Mill offers two arguments: those who hold erroneous beliefs are more likely to abandon them in a free exchange of ideas, while vigorously contesting a true belief prevents it from becoming an unexamined prejudice or dogma.

In fact, conspiracy theorists rarely abandon their beliefs through a free exchange of ideas. Conspiracy theories have a “self-sealing” property, whereby new information that challenges the belief comes to be seen as further proof of it. If you try to convince a “9/11 truther” that the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks were not, in fact, an inside job, they will probably lament that you have been brainwashed, too, and urge you to read a report or watch a documentary showing that the official version of history is a lie.

The point to remember is that conspiracy theorists genuinely believe that a small secret group of people – a cabal – controls the world. With this as one’s premise, it makes sense to interpret all new information as validation of it.

Should we therefore stifle conspiracy theorists in the interest of facilitating a rational exchange of ideas? Mill, who opposed all forms of censorship, argued that such a public intervention is justified only on the basis of the “harm principle.” As he famously put it in On Liberty: “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.”

Considered in isolation, many conspiracy theories do not fall afoul of Mill’s principle. Simply believing that aliens have landed at Roswell, New Mexico, or that no one landed on the moon doesn’t hurt anyone, though otherwise harmless conspiracy theories can of course encourage harmful acts. For example, the belief that 5G technologies help to propagate COVID-19 has led people in the UK to burn down cell towers.

Moreover, conspiracy theories sometimes do inflict direct harm, as is often the case when they are linked to anti-Semitism. It might not matter that the British conspiracy theorist David Icke believes lizards are ruling the world; but it does when he lashes out against “Rothschild Zionists.” Going back at least as far as the notorious Czarist secret police fabrication, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, Jews have been the conspiracy theorist’s cabal par excellence, which helps to explain why figures such as George Soros remain the subject of conspiracy theories – and the target of threats and defamation – to this day.

Similarly, many of those who violently attacked the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, subscribe to the QAnon conspiracy theory, which holds that Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Soros are part of a Satanist, pedophilic child sex-trafficking ring. In this case, the US has a number of legal measures designed to encompass the negative effects of conspiracy theories, such as “breach of peace” ordinances and laws against disorderly conduct or “hate speech.”

But, again, these statutes address individual actions, not the beliefs themselves. The problem with vaccine hesitancy is not the belief that Gates is trying to implant a microchip into your brain; it is the act of not getting vaccinated. What, if anything, can the state do about that?

Evidence from the UK suggests that as more people get vaccinated, vaccine hesitancy declines. The UK and US both started with similar levels of “anti-vax” sentiment last summer, but such views have plummeted in the UK, and the country is now outpacing the US in vaccinations. This suggests that as more people get vaccinated and see that everything is okay, others may be more likely to follow suit.

The best way to create this virtuous cycle is not to censor conspiracy theories but rather to vaccinate more people and spread the message that vaccines are indeed safe and effective. Seeking to prevent false beliefs from being aired simply gives ammunition to those claiming that the state is out to get them.

For the final holdouts, vaccine mandates might be the only solution, particularly if countries remain far short of herd immunity. With the highly contagious Delta variant ravaging communities with lower rates of vaccination, this would be a true application of Mill’s “harm principle”: to prevent harm to others.

As Mill observed, all beliefs are either wholly false, partly true, or wholly true. In the case of conspiracy theories, we should remember that many are often based on some grain of truth, or at least on a legitimate impulse to challenge the elite consensus. No, Gates doesn’t want to control our minds with microchips; but it is perfectly reasonable to worry that today’s tech giants have too much influence over the way we think.

Exploring these nuances is what Mill meant when he advocated for the vigorous public contestation of true beliefs. Though we might beat the pandemic eventually, the battle for critical thinking will go on.

Why Vaccination Should be Compulsory

Although the first compulsory seat-belt laws met with strong objections when they were introduced 50 years ago, nobody bothers to complain about such a commonsense rule anymore. In mandating vaccination against COVID-19, governments today can offer the same basic justification for protecting both individuals and society.

MELBOURNE – I’m writing from Victoria, the Australian state that became, in 1970, the first jurisdiction in the world to make it compulsory to wear a seat belt in a car. The legislation was attacked as a violation of individual freedom, but Victorians accepted it because it saved lives. Now most of the world has similar legislation. I can’t recall when I last heard someone demanding the freedom to drive without wearing a seat belt.

Instead, we are now hearing demands for the freedom to be unvaccinated against the virus that causes COVID-19. Brady Ellison, a member of the United States Olympic archery team, says his decision not to get vaccinated was “one hundred percent a personal choice,” insisting that “anyone that says otherwise is taking away people’s freedoms.”

The oddity, here, is that laws requiring us to wear seat belts really are quite straightforwardly infringing on freedom, whereas laws requiring people to be vaccinated if they are going to be in places where they could infect other people are restricting one kind of freedom in order to protect the freedom of others to go about their business safely.

Don’t misunderstand me. I strongly support laws requiring drivers and passengers in cars to wear seat belts. In the US, such laws are estimated to have saved approximately 370,000 lives, and to have prevented many more serious injuries. Nevertheless, these laws are paternalistic. They coerce us to do something for our own good. They violate John Stuart Mill’s famous principle: “the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.” The fact that the coercion is for the individual’s own good is “not a sufficient warrant.”

There is a lot to be said for this principle, especially when it is used to oppose laws against victimless acts like homosexual relations between consenting adults or voluntary euthanasia. But Mill had more confidence in the ability of members of “civilized” communities to make rational choices about their own interest than we can justifiably have today.

Before seat belts were made compulsory, governments ran campaigns to educate people about the risks of not wearing them. These campaigns had some effect, but the number of people who wore seat belts came nowhere near the 90% or more who wear them in the US today (with similar or higher figures in many other countries where not wearing them is an offense).

The reason is that we are not good at protecting ourselves against very small risks of disaster. Each time we get into a car, the chance that we will be involved in an accident serious enough to cause injury, if we are not wearing a seat belt, is very small. Nevertheless, given the negligible cost of wearing a belt, a reasonable calculation of one’s own interests shows that it is irrational not to wear one. Car crash survivors who were injured because they were not wearing seat belts recognize and regret their irrationality – but only when it is too late, as it always is for those who were killed while sitting on their belts.

We are now seeing a very similar situation with vaccination. Brytney Cobia recently posted on Facebook the following account of her experiences working as a doctor in Birmingham, Alabama:

“I’m admitting young healthy people to the hospital with very serious COVID infections. One of the last things they do before they’re intubated is beg me for the vaccine. I hold their hand and tell them that I’m sorry, but it’s too late. A few days later when I call time of death, I hug their family members and I tell them the best way to honor their loved one is to go get vaccinated and encourage everyone they know to do the same. They cry. And they tell me they didn't know. They thought it was a hoax. They thought it was political. They thought because they had a certain blood type or a certain skin color they wouldn’t get as sick. They thought it was ‘just the flu.’ But they were wrong. And they wish they could go back. But they can’t.”

The same reason justifies making vaccination against COVID-19 compulsory: otherwise, too many people make decisions that they later regret. One would have to be monstrously callous to say: “It’s their own fault, let them die.”

In any case, in the COVID era, making vaccination compulsory doesn’t violate Mill’s “harm to others” principle. Unvaccinated Olympic athletes impose risks on others, just as speeding down a busy street does. The only “personal choice” Ellison should have had was to get vaccinated or stay at home. If the International Olympic Committee had said that only vaccinated athletes can compete, that would have freed thousands of athletes from a heightened risk of infection, and would have justified overriding Ellison’s desire to compete without being vaccinated.

For the same reason, rules announced last month in France and Greece requiring that people going to cinemas, bars, or traveling on a train show proof of vaccination are not a violation of anyone’s freedom. This past February, when the Indonesian government became the first to make vaccination mandatory for all adults, the real tragedy was not that it was violating the freedom of its citizens, but that richer countries did not donate the vaccines it needed to implement the law. As a result, Indonesia is now the epicenter of the virus and tens of thousands of unvaccinated Indonesians have died.

The Rich World’s Super-Spreader Shame

G20 countries have failed the rest of the world during the pandemic, not least by serving as viral super spreaders. To make up for it, they must follow through on global vaccination commitments and establish new international standards for pathogen surveillance and travel.

OXFORD – G20 leaders will meet in Rome at the end of October, in part to discuss how to deal with future pandemics. But the truth is that their countries’ actions have largely fueled the current one.

Many G20 countries have been COVID-19 super spreaders. Following the coronavirus’s transmission beyond China, which initially sought to quash reporting of the outbreak, the United States and other rich countries chalked up early failures that greatly contributed to the virus’s worldwide spread. Had they acted sooner, they could have at least slowed its transmission to poorer countries. Worse still, their failure to commit to vaccinating the whole world as quickly as possible has created a self-defeating cycle where more transmissible and harmful variants of the virus are likely to be unleashed.

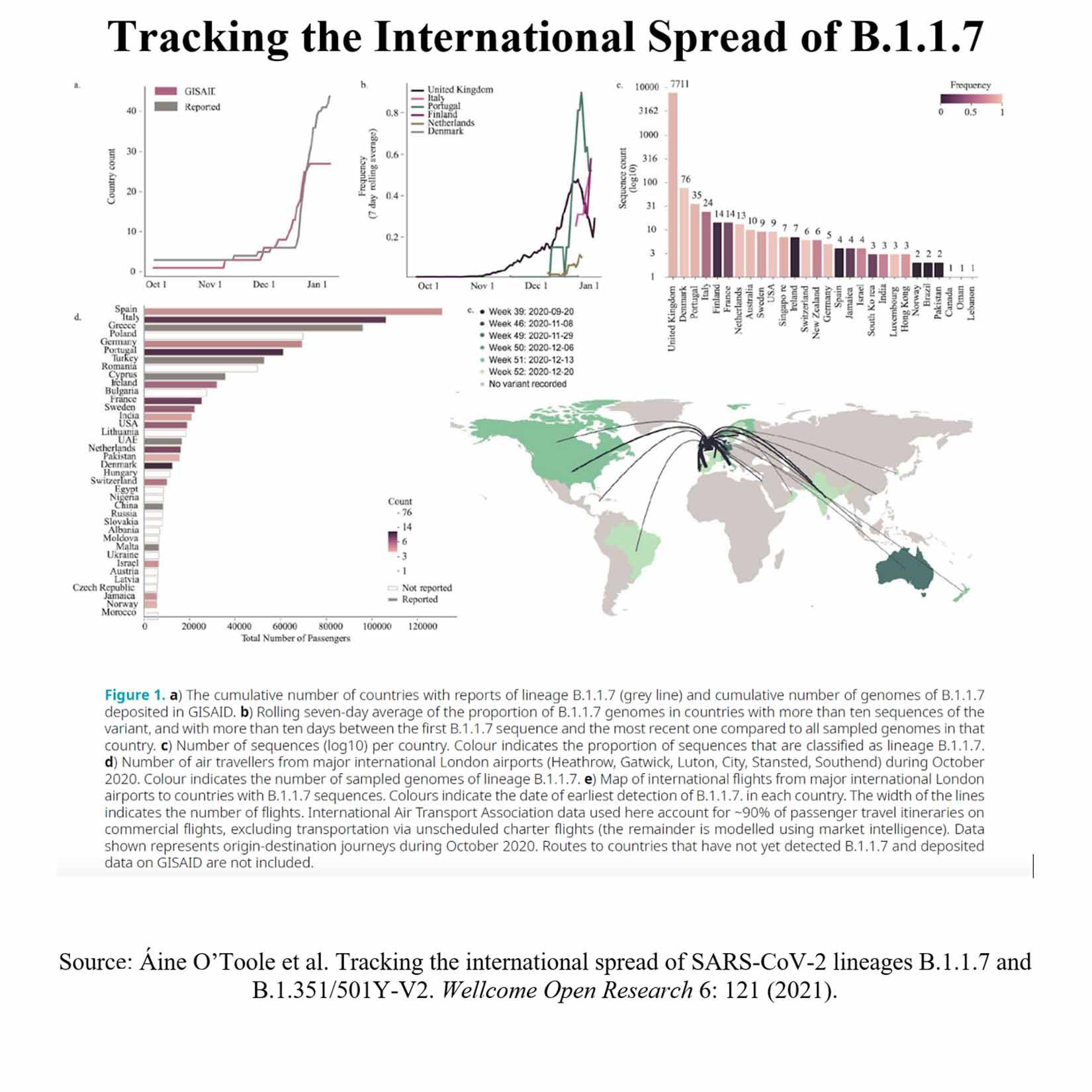

Statistical models show that international air travel was the key factor in the global spread of COVID-19 until early March of last year. This is borne out by the charts below, which detail the spread of the Alpha variant (also known as the UK or Kent variant) and the frequency of air travel to different countries from London airports in October 2020. Prominent in the Alpha variant’s spread were Spain, Italy, and Germany.

Data from earlier in the pandemic enable us to see how different viral strains emerged over time. If we put this information alongside data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) regarding government policies, we can pin down the details of disease spread. Among G20 countries, the failures of the US and the United Kingdom stand out.

New York was one of the early super-spreader cities. It recorded its first confirmed COVID-19 case on February 29, 2020, about a month after the US restricted travel from parts of China. But even though COVID-19 was raging in Italy, the US introduced restrictions on people arriving from mainland Europe only on March 13, two days after the World Health Organization declared a pandemic; and not until March 16 did it extend these to arrivals from the UK and Ireland.

The viral sequence data demonstrate that the virus did not move directly from China to New York. Instead, US hesitancy to clamp down on travel from Europe was largely responsible for multiple introductions of the virus, which seeded the city’s huge death toll.

Moreover, interstate travel within the US largely continued during lockdowns. OxCGRT data show that 17 US states have never stopped it since the pandemic hit. The similar mix of viral lineages from early in the pandemic across the US indicates that reintroductions of the virus were common even in places that had eliminated an original strain. Research combining air-travel data and genomics has concluded that the spread of COVID-19 within the US resulted more from domestic introductions than international air travel.

The UK was another super spreader with an achingly slow pandemic response, given where and when genomics now tells us the virus was circulating. In that regard, the COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium (COG-UK), the largest of its kind in the world, has sequenced more than 26,000 viral isolates from people who caught COVID-19 in the UK’s first wave, and compared these sequences with those from other countries.

Two main conclusions emerge. First, Europe was the source of initial infections in the UK. Up until late June 2020, 80% of imported viruses arrived in the month-long period from February 27 to March 30, and these were overwhelmingly from Europe. One-third of them came from Spain, 29% from France, and 12% from Italy – and a mere 0.4% from China.

Second, inbound travel fueled the arrival of many new genetic lineages in the UK, with the rate of these appearances among the infected population peaking in late March 2020. When the UK then finally brought in non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) en masse – causing the country’s score on the OxCGRT Stringency Index to rise from 17 out of 100 to almost 80 in just one week – the diversity of viral isolates began to decline. In other words, the NPIs succeeded in extinguishing many of these lineages in the UK.

These failures cast doubt on G20 countries’ pandemic management more broadly. Had the world’s large, advanced economies stopped new arrivals earlier (especially travelers from Europe), and had they limited internal travel, they would have reduced their own COVID-19 devastation.

Restricting the export of infections would have slowed or perhaps even largely prevented the disease’s spread to poorer countries until vaccines were developed. That, in turn, might have averted costly lockdowns in places that could ill afford them. G20 governments have focused on preventing the import of the virus, not its export. With hindsight, the virus would have been contained had they required repeat negative tests for anyone getting on a plane or emerging from a quarantine facility.

Having accelerated the spread of COVID-19, richer countries are now prevaricating about getting vaccines to those who need them most. Wealthy countries have stockpiled doses, prioritized vaccinating children who are at relatively very low risk from COVID-19, and are even preparing third “booster shots” for which there is no evidence yet of widespread, near-term need.

Meanwhile, COVID-19 is ravaging developing countries, where frontline health workers are dying because they have no access to vaccines. The pandemic has already killed more people globally in 2021 than it did in 2020. Many experts harbor grave concerns about the further spread of the Delta variant, as well as other variants to come, especially in regions where vaccination is progressing slowly.

G20 countries must make up for their COVID-19 failure and commit to vaccinating those at most risk across the world. And as super-connected countries, they must also establish new international standards for pathogen surveillance and travel protocols to ensure that they never super-spread again.

Investing in Global Vaccine Equity Acknowledges Our Shared Fate

Vaccines are among modern medicine’s greatest innovations, allowing billions of people to lead healthy lives. But stopping outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease – and not only COVID-19 – depends on achieving critical mass with immunization campaigns.

NAIROBI – The extraordinary global effort to develop safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines in record time highlights the power of vaccines to bring us closer to our loved ones and to a more prosperous, equitable world in which everyone has the chance to achieve their full potential. Vaccines are among modern medicine’s greatest innovations, allowing billions of people to lead healthy lives. But stopping outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease – and not only COVID-19 – depends on achieving critical mass with immunization campaigns.

Consider polio. The shuttering of classrooms to protect children from COVID-19 outbreaks might seem unprecedented, but a 1937 polio outbreak in the United States inspired school-by-radio programs – an early innovation in remote learning. In those days, polio was thought to afflict only industrialized countries, until a major outbreak in South Africa in 1948 led to the establishment of the first African foundation for polio research and catalyzed greater awareness of the disease’s global burden. In the 1950s, polio paralyzed an average of 600,000 people each year.

Fortunately, scientists developed the first polio vaccines later that decade. And since the launch of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in 1988, vaccines have reduced the global incidence of wild polio cases by more than 99%, from hundreds of thousands annually to a handful of endemic cases in just two remaining countries: Afghanistan and Pakistan. In 2020, Africa was certified as being free of wild polio, giving the continent a much-needed glimmer of hope amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Strong vaccine coverage has made it possible to believe that polio could become the second disease – after smallpox – to be eradicated through vaccination.

But the polio clock has not stopped ticking: back in 2014, the World Health Organization sounded the alarm when it designated the disease as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. In particular, areas with low immunization rates, and thus low levels of protection, are also vulnerable to rare but increasingly frequent outbreaks of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV), which occur when the weakened pathogen originally contained in oral polio vaccines eventually regains virulence.

Today, cVDPV outbreaks outnumber wild polio cases. Although we are closing in on the virus, we are struggling to maintain the strong vaccine coverage needed to stop these outbreaks before they start, owing to a lack of resources, conflict or civil unrest, and pandemic-related disruptions to immunization drives.

The COVID-19 crisis has so far caused the postponement of 57 lifesaving mass vaccination campaigns in 66 countries, affecting hundreds of millions of people, mostly African children. In November 2020, the WHO and UNICEF called for emergency action to avert a secondary crisis of measles and polio outbreaks caused by disrupted vaccine access.

Even as we rally together against COVID-19, PATH and other partners continue to call upon national governments and donors to double down on immunization against polio and other vaccine-preventable diseases. The newly launched Immunization Agenda 2030 global framework has a crucial role to play both to make up for lost time and to boost our collective resilience. As the pandemic has shown, cross-border spread of infectious disease is an ever-present threat. All therefore have a strong interest in international immunization coverage.

Investing in disease prevention through vaccine development and delivery protects us all and will pay dividends for years to come. We should thus feel heartened by the stunning speed with which the scientific community – helped by many previous years of research into other coronaviruses – came together to develop effective COVID-19 vaccines.

These investments are bearing fruit not only for COVID-19, but also for polio. Last year, after a decade of research and development, the novel oral polio vaccine against type 2 (nOPV2) became the first vaccine to receive a WHO Emergency Use Listing. Researchers expect that nOPV2 will be less likely to seed new cVDPV2 outbreaks, thereby helping to hasten the eradication of polio.

When it comes to highly infectious diseases such as COVID-19 and polio, our fates are bound up together; what affects one part of the world affects us all. Investing in tools for a single country does little to a control or eliminate such global health threats. Instead, we must keep global vaccine access at the center of our efforts. Strong national commitments and financing for the Immunization Agenda 2030 framework can help get us there.

Globalization has already brought us closer together. With a commitment to equitable immunization access, the world can advance toward a shared future of health and prosperity.

CAMBRIDGE – On May 14, 1962, the agriculture commissioner of Montana, Lowell Purdy, launched what would become one of the century’s great platitudes. “If we can put a man on the Moon,” he declared, seven years before the United States achieved President John F. Kennedy’s goal, “we surely are capable of seeing that our temporary surplus agricultural products are placed in many hungry stomachs of the world.”

Since then, the formula has become a cliché – precisely because it often makes a pretty good point. Today, for example, one might point out: “If we can produce vaccines that drastically decrease the transmission and severity of COVID-19, we surely are capable of ending the pandemic.” And yet, we have so far been unable to do so, largely because people simply refuse to be vaccinated.

To be sure, in some cases – especially in lower-income countries – the primary impediment to large-scale immunization is limited vaccine availability. But in a country like the US, the main problem is vaccine hesitancy, even hostility. Although the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency approval to three vaccines – a process that demands rigorous testing – many are convinced they are still “experimental,” and thus unsafe.

As Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the US National Institutes of Health, put it, there are two Americas, and their perceptions regarding vaccination are separated by a wall. For the America that mistrusts vaccines, the expertise of remote authorities and the logic of the scientific method are unconvincing.

Perhaps more tangible, real-world evidence can change their minds. It is certainly piling up: recent data show a strong negative correlation between vaccination rates and rates of infection, hospitalization, or death from COVID-19 across the US. In the week that ended on June 22, counties where 30% or fewer residents had been vaccinated suffered 5.6 new COVID cases per 100,000 people, whereas counties where more than 60% of residents had been vaccinated experienced just 2.1 new cases per 100,000.

On updated data, a one percentage-point increase in the share of adults (and teenagers) who were fully vaccinated in a given county as of June 9 was associated with a significant decline in the COVID-19 death rate – 0.06 per 100,000 inhabitants – over the subsequent 30 days (to July 9). That represents 2% of the total monthly coronavirus-related deaths. One could extrapolate from this that the statistical effect of reaching 100% vaccination would be to bring COVID-related deaths close to zero.

But, of course, correlation does not prove causality. The apparent beneficial effect of vaccination could, one might argue, be the result of some third factor, such as poverty. Low-income people are at higher risk of becoming infected with and dying from COVID-19, owing to a range of factors, from housing conditions to types of employment. If they are also less likely to get vaccinated, it could create the illusion that lack of immunization is the problem. Yet the beauty of econometrics is that one can control for third factors, such as the poverty rate or local temperature, to isolate statistically the effect of vaccination rates.

But this does not fully resolve the causality question. There is also the possibility that the simple observed correlation between vaccination and mortality understates the true impact of the vaccines. After all, those living in a high-risk context – say, near a transport hub – are more likely to know people who have suffered from the coronavirus, and thus might be more likely to get vaccinated. This “reverse causality” could lead to an apparent – and excessive – positive correlation between vaccination and death rates.

And, in fact, this could partly explain why earlier studies, conducted as recently as the beginning of June, did not find a clear negative correlation. But, as the highly contagious Delta variant gains traction among the unvaccinated, the correlation between immunization and lower COVID-19 infection and death rates is strengthening.

Still, to have a chance of convincing the vaccine skeptics, it is vital to disentangle causality from correlation. The key is to look at variations in vaccination rates that have nothing to do with where and how the coronavirus spreads – indeed, have nothing to do with the coronavirus at all. In technical parlance, we need an “exogenous instrument.”

Party affiliation or voting patterns are an obvious choice. Throughout the pandemic, Republican governors have been less likely than their Democratic counterparts to support public-health measures, such as mask mandates. Not surprisingly, Republican voters (45%) are less likely than independents (58%) and Democrats (73%) to accept vaccines. In counties where then-President Donald Trump won by a margin of 50 percentage points or more in the 2020 election, the vaccination rate was below 25%, as of April 17.

The “partisan gap” – which continues to widen – holds even after accounting for income, race, and age, as well as population density and the local infection and death rates. According to my calculations, when controlling for the poverty rate and other relevant variables (particularly age and temperature), a one percentage-point increase in the share of a county’s residents over age 12 who were fully vaccinated as of June 9 is associated with a death rate that was 0.05 lower per 100,000 inhabitants during the subsequent 30 days.

To ensure that the results are not distorted by reverse causality, I also performed another calculation, based on the same data. Accounting for variation in the vaccination decision attributable solely to partisan political affinity – and controlling for variables like poverty – I found the difference in the COVID-19 death rate to be 0.04 per 100,000 inhabitants.

I used voting patterns not to target any particular group, but rather to provide a better estimate of vaccine effectiveness on anyone. But I hope that at least some skeptics notice that members of their political “in-group” are dying at a higher rate, and decide to give vaccination a chance. As Rochelle Walensky, the director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, recently observed, “This is becoming a pandemic of the unvaccinated.”